Ari Armstrong's Web Log (Main) | Archives | Terms of Use

Sheriff Bill Masters's Critique of the Drug War

Archival photos and notes about Sheriff Bill Masters, Colorado's longest-serving sheriff.

by Ari Armstrong, Copyright © 2025

Sheriff Bill Masters is the longest-serving sheriff in Colorado history, having served as a peace officer for fifty years and as sheriff of San Miguel County from 1980 to 2025. Masters joined the Telluride Marshal's Department in 1975, became undersheriff in 1979, was appointed sheriff in 1980 when Fred Ellerd left the position for the county commission, and won his first election for sheriff in 1982. Masters retired from on June 2, 2025, and Dan Covault became interim sheriff.

I was involved in editing, preparing, and promoting Masters's two books, Drug War Addiction (2001) and The New Prohibition (2004, essays edited by Masters). I also was involved in the Libertarian Party of Colorado at the time, which Masters joined for a few years.

See also my 2024 interview with Masters.

Images courtesy of Bill Masters and Ari Armstrong. David Shinn took some of the photos around 2003, and also took the photo on the cover of Drug War Addiction.

Drug War Addiction

The complete text of Bill Masters's 2001 book, Drug War Addiction: Notes from the Front Lines of America’s #1 Policy Disaster, now is published online.

The New Prohibition

The complete text of Bill Masters's edited 2004 book, The New Prohibition: Voices of Dissent Challenge the Drug War, now is published online.

Media

"Sheriff Bill Masters: Telluride Sheriff Just Says No to the Drug War," Nancy Lofholm, Denver Post, August 28, 2000.

"Sheriff scoffs at drug war," Barry Bortnick, Gazette, December 10, 2001 (link not available).

"Gunning and Drugging for freedom," Wayne Laugesen, Boulder Weekly, November 29, 2001 (link not available).

"New book continues drug war debate," Michael Holzmeister, La Voz Nueva, May 26, 2004 (link not available).

"Libertarians Challenge the Drug War," Bob Ewegen, Denver Post, June 1, 2002 (link not available).

"Dare to challenge the drug war," Vince Darcangelo, Boulder Weekly, July 8, 2004 (link not available).

"Debunking the 'war on drugs,' libertarian style," Clay Evans, Daily Camera, July 11, 2004 (link not available). Evans writes, "The essays reveal in stark, practical terms how the government has wasted billions of taxpayer dollars on the drug war only to drive up prices—which then attracts new, profit-seeking daredevils to the business. Supply and demand, remember? They show that the war's ammunition falls disproportionately on minorities, and how prisons rife with drugs may actually make addicts worse."

"It's time to rethink and reform drug laws," Denver Post lead editorial, September 5, 2004 (link not available). The piece says, "Masters, Kane and others make a compelling argument that the problems with some drugs, notably marijuana, are actually magnified by the current prohibition policy. . . . The wide-ranging authors of "The New Prohibition" have performed a signal service by highlighting the current drug war as a microcosm of the inevitable failures of a federal nanny-state mentality."

"Sheriff celebrates 45 years of service to San Miguel County," Mia Rupani, Telluride Daily Planet, January 16, 2024.

"The Maverick," Alan Prendergast, Westword, May 20, 2004.

"Bill Masters, Colorado's longest serving lawman, reflects on a half century of service," Jason Blevins, Colorado Sun, May 4, 2025.

"Local Legends: Bill Masters," Emily Shoff, Telluride News, May 23, 2025.

2025 Statement on Immigration Enforcement

In one of his last public statements as sheriff, Masters released the following statement on May 2, 2025, regarding the "Trump Administration's Attempt to Federalize Sheriffs Offices":

I strongly support the investigation of and arrest of all persons, regardless of their citizenship or immigration status, who commit serious crimes. Over the past 50 years, I have arrested dozens of undocumented persons and at times their human smugglers, sometimes by the van load. To this day, the Sheriff's Office cooperates within the confines of Colorado law with our federal partners, and vigorously investigates and arrests those persons who have active arrest warrants issued for their detention that have been reviewed, approved, and signed by a judge as Colorado law and the US Constitution require. This executive order is an attempt to federalize, by intimidation, the San Miguel County Sheriff's Office to do the current administration's bidding on their political cause of the day. Not since the Runaway Slave Act of 1850 has the Federal Government attempted to federalize and use local peacekeepers to fulfill its political objectives. Many Sheriffs of that era refused to enforce (even under penalty of law) the Runaway Slave Act. As concerned as I am regarding federalization of local peacekeepers for immigration enforcement, I also see this current attempt as opening the door for future administrations to consider requiring local Sheriffs to enforce federal laws to arrest firearm owners, political opponents, protestors, etc. Although I am Sheriff of this great county for only another 30 days, I want to assure our local residents that during my short remaining tenure, I will follow Colorado law and not permit the federal government to use my office for political purposes.

Photos

Masters in the Coast Guard, 1971

Masters in the town marshall's office, 1975

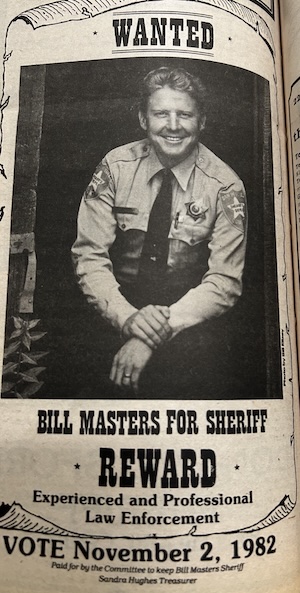

An ad for Masters's first election in 1982

Masters with his mom, 1992

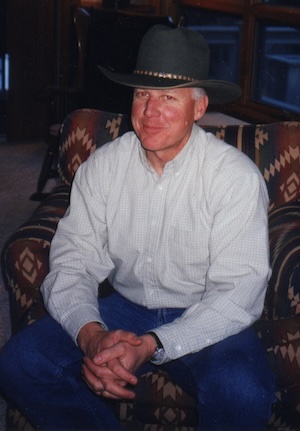

Masters, undated

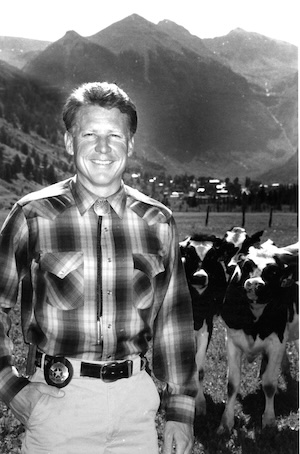

Masters with the cows, undated

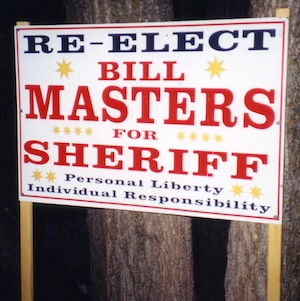

A reelect Bill Masters sign, undated

Masters speaking at the Libertarian Party national convention, 2000

Masters appeared on 9News, 2001

Masters with Gregg Stone of KBPI, when Masters appeared on the radio with Stone, 2001

Masters on the radio with Reggie Rivers, 2001

Masters on WB2 TV, 2001

Masters delivering a talk at the University of Colorado, Boulder, 2001

Masters with CU Campus Libertarians, 2001

Masters speaking in Grand Junction, 2001

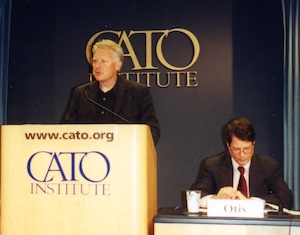

Masters addressing the Cato Institute, 2002

Masters on CNN, 2002

Masters at the Washington Monument, 2002

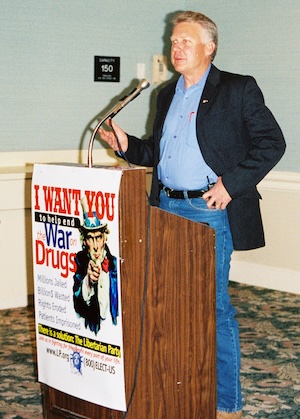

Masters addressing a Colorado Libertarian event, 2002

Masters, 2003, photo by David Shinn

Masters, 2003, walking down the streets of Telluride, photo by David Shinn

On July 13, 2004, Bill Masters and several contributors to The New Prohibition spoke at Boulder Bookstore. From left to right are Mike Krause, Judge John Kane, Michael Huemer, David Kopel, and Ari Armstrong.

Judge Kane and Huemer

Huemer and Kopel

Mike Krause

Judge Kane

2001 Op-Ed

The following op-ed by Bill Masters was published by the Denver Post on May 13, 2001.

Time to change strategies

by Bill Masters

Roni Bowers and her baby Charity were killed not by drug dealing gangs or criminal thugs, but instead by government agents. They were "collateral damage" in the war on drugs.

In late April, a United States spotter aircraft, flying with a Peruvian air force officer on board, thought a civilian plane might have been transporting drugs. However, the only cargo was a human one of Baptist missionaries and their children, including 7-month-old Charity and her mother.

After spotting the civilian aircraft, the U.S. jet contacted the Peruvian air force, which then scrambled fighters to shoot at the helpless civilians.

A bullet went through Roni and into her baby, killing them both instantly.

Witnessing this horror were Roni's husband, Jim, and their 6-year-old son, Cory, who were passengers on the plane. During the attack, the pilot of the civilian plane continued contact with civilian Peruvian air traffic controllers. According to press reports he said repeatedly, "They are killing us! They are killing us!"

After the plane was strafed, the American pilot working for the Baptist church was able to crash the burning plane into a river. The injured pilot together with Jim and Cory were able to escape the wreckage and float down the river grasping dislodged pieces of aircraft. One fighter plane continued to shoot at them. Reuters reported that the U.S. plane watched the incident from about a mile away.

We shouldn't be surprised that this occurred. Mad as hell maybe, but not surprised. After all, we are in a war, a war on drugs. And during times of war innocent people get in the way.

This tragedy has played itself out scores of times in recent years.

U.S. Marines shot and killed teenage goat herder Esequiel Hernandez in 1997 near his home in Texas, mistaking him for a drug runner.

Drug agents flew over 62-year-old Donald Scott's ranch and claimed they saw marijuana growing on his property. They raided his home, pushed his wife to the ground and shot him to death. No drugs were found.

Police, acting on false information about a $30 drug deal, raided the home of 84-year-old, bed-ridden Anna Rae Dixon and shot her with a 12-gauge shotgun, killing her instantly.

In Denver, Ismael Mena was killed in September 1999 after a cop filed a false search warrant affidavit and the SWAT team raided the wrong home. Reportedly the last word from the father of nine was a questioning "Policia?" as the dressed-in-black SWAT team stormed into his small room.

The list goes on and on. It includes children, mothers, fathers, elderly ladies and teenage goat herders. All "collateral damage," according to common military parlance.

The increasing militarization of the drug war and our local police forces is a dangerous trend. Today most of the tactical and firearms training for "peace" officers comes straight out of military doctrine. The tactics taught are not of negotiations or individual bravery but of concentration of forces and firepower.

In our own state, the legislature has passed laws requiring the governor "as commander in chief" to use the soldiers of the Colorado National Guard for drug interdiction and enforcement. To that end, the soldiers are providing "aviation assets and ground assistance units trained for the specific mission of cannabis suppression and eradication." They are available to local law enforcement in "narcotics-centered investigations with surveillance platforms, thermal imagery and night vision equipment, case support and intelligence analysis."

The soldiers are also training local officers at the County Sheriffs of Colorado facility in Douglas County on issues like "non-urban tactical operations" and "airmobile drug enforcement operations."

It is only a matter of time before our increasingly militarized tactics will result in more unintended deaths like those in Peru. I question whether it is worth it.

Policing and blaming Peru, Colombia or Mexico for our nation's drug problems is a little like blaming Saudi Arabia for traffic jams. This is a demand problem, not a supply problem.

We shut off the cocaine supply, then some people start cooking meth in their homes. We stop the meth and many will get high on Ecstasy, booze, the doctor's pills or whatever. Controlling the drug supply is like holding water in a fist, it just leaks out and goes on to something else.

Eventually we will realize a fist won't work against what is fundamentally a spiritual problem.

Before we suffer more innocent deaths at the hands of those sworn to protect us, before we lose touch with our local peace officers, and before more children overdose because we haven't identified or addressed the demand problem, we must rethink the drug war. We must change strategies.

Material for Drug War Addiction

Sheriff Bob Braudis (Pitkin County, Colorado), said, "An early pioneer . . . Bill has let the genie out of the bottle... He has an awful lot of courage for stating this. . . . If you have a drug problem you should go to the doctor, not to jail."

Sheriff Bill Masters fought the "Drug War." He was good at it. He even won an award from the Drug Enforcement Agency. Through his real-world experiences as a law officer, Masters concluded drug prohibition must be repealed. He discovered the drug war is itself an addiction, more damaging to the fabric of American society than drugs could ever be.

Masters has served as sheriff of San Miguel County (County Seat: Telluride), Colorado, since 1980, and he is the nation's first Libertarian sheriff. He argues police should spend their time getting violent criminals off the streets. He also seeks cultural renewal in our nation by returning to the principles of personal responsibility, simple laws, and limited government. In this book, Sheriff Bill Masters explains why we need to kick our nation's drug war addiction.

Review by Judge John L. Kane

John L. Kane, Senior U. S. District Court Judge in Denver, reviewed Drug War Addiction for the Sunday, February 24, 2002, edition of the Denver Post, page 3EE.

Sheriff levels blast at Drug War

Years ago, the sheriff of a Colorado mountain county was approached by an informant. A load of meth was entering the state from California.

The tip was good: The informant knew who was picking up the load, what type of car would be used, the date it was due to arrive and where it was going. The dealers lived in a neighboring county. The sheriff filed his report with the Colorado Bureau of Investigation and passed the tip on to the sheriff in the county where the dealers lived.

Imagine his surprise when, more than a year later, the very sheriff he had warned was arrested along with key members of his staff for running the meth-dealing ring.

Was that the defining moment for Bill Masters, sheriff of San Miguel County -- the idealistic officer who received the informant's tip and dutifully passed it on? He served on the front line of the War on Drugs even before he was appointed sheriff in 1979 [actually 1980]. He is the recipient of an award for outstanding achievement from the US Drug Enforcement Administration.

Masters had made numerous drug-related arrests and led countless more investigations. Today, he is one of this county's leading opponents of the drug war. In "Drug War Addiction," Masters tells us what knocked him off the war horse.

The son of a Marine who served in the South Pacific during World War II, Masters grew up in Los Angeles. After enlisting in the Coast Guard, he became a law enforcement officer. First elected as a Republican and then as a Libertarian who won 80 percent of the vote, he is now in his fifth term as sheriff of San Miguel County.

When Sheriff Masters takes us along with him on police training, investigations and arrests, he clearly knows whereof he speaks. It is his unique vantage point that makes "Drug War Addiction" such a valuable addition to the growing dialogue on the far-reaching effects of out country's most recent experiment with Prohibition. Indeed, according to Masters, America is addicted to its domestic war.

"The first way the drug war has become an addiction," he writes, "is obvious: law enforcement agencies are addicted to the money." Not only does that enable police departments to pay the salaries of additional staff, it also buys them guns and high-tech surveillance equipment. As famed economist and Nobel Laureate Milton Friedman has pointed out, local agencies benefit not just from this multibillion-dollar bonanza, but from the forfeiture of assets of suspected drug dealers.

In making them a beneficiary of its largesse, the drug war at the same time diverts law enforcement from pursuing its primary mission and appointed task of protecting the public against violent crime.

In regard to forfeiture, it isn't even necessary to charge or convict a suspect in order to seize his property; in fact, it's far simpler to threaten prosecution and take property in lieu of giving the suspect his day in court. Herein lies Master's second powerful point; the extent to which police departments are corrupted by drug prohibition.

It is often said that familiarity breeds contempt. It is equally true that familiarity breeds corruption. While it is impossible to know with the precision the extent to which law enforcement has been corrupted by the drug war because many infractions amount to just looking the other way or taking "a little cream off the top" from known dealers. The General Accounting Office has found that between 1993 and 1997, on average, half of all FBI - led - investgations into police misconduct were related to drug offenses. These investigation go all the way up to theft, perjury and murder.

The human face Masters puts on the corruption of law enforcement is his most indelible contribution. "Drug War Addiction" refreshes the national dialogue with poignant examples that bring the devastation and apparent futility of the War on Drugs all too painfully close to our doors. Masters writes from the battle zone. Both supporters of the drug war and those who believe it is a failure will benefit from this brave warrior's message.

DRCNet Interview

The Week Online with DRCNet (Issue #220), January 18, 2002, a publication of the Drug Reform Coordination Network, published an interview with Sheriff Masters. The interview was reprinted in LP News.

Q: You've been sheriff for 22 years. What prompted you to write this book now?

Sheriff Bill Masters: I've been speaking my mind on this and other issues for awhile now, even though I bought into the drug war when I became a cop. I thought it was my duty to enforce the drug laws. I had a policeman mentality, which is not bad, except when the laws you're enforcing become oppressive. But I'm basically a Barry Goldwater-style conservative, and I think people should control their own bodies. After awhile, I saw that we spend more and more money and arrest more and more people and have more and more drugs. It doesn't take a rocket scientist to figure out that this policy is not working. People need to look at this rationally and ask if this is effective. Do we have a healthier society because of drug prohibition? Drug dealers are certainly wealthy because of it. The reason drugs have expanded so much is there is a profit to be made in drug dealing. We need to eliminate that profit motive. At any rate, some libertarian friends of mine looked at some of my speeches and told me I needed to write a book. I played around with writing some novels, but kept going back to the abundance of laws that try to control human behavior. So I tied to write about libertarian ideas and about the drug war. I passed it around to some literary critics in the area, and they said no one would ever publish it. But we got publishers bidding on it. We might even sell a few.

Q: What kind of reaction are you getting from the law enforcement community? What about the feds?

Masters: Definitely a mixed bag. A few sheriffs and others come out and say "Bill, you're absolutely right." But those are people who are very secure in their positions. They have strong community support because they are stand-up people. Others feel they have to be strong drug warriors, they say the community demands it. But I tell them that maybe they're misjudging their public. They don't want to hear that, but you have to lie to yourself if you think you can arrest yourself out of this problem. But I did that for years, I played the hard guy, I used it to get elected. As for the DEA, they haven't said anything. They've given me assistance every time I called them, they haven't given me a hard time, they've acted professionally around me.

Q: Colorado drug laws are still on the books. You presumably have to enforce those laws. What, given your views on drug prohibition, do you do differently?

Masters: First off, police officers have tremendous amounts of discretion, and we consciously choose our priorities. If there's a crime against a person, that's top priority and everything else stops. Same thing with traffic problems, we take them seriously, too. But we have to take the drug issue seriously, too; we don't want people thinking they can come here and be meth heads. About 10% of our arrests are for drugs. As for raids, I've learned I was doing a disservice to my community. We've got to be more careful in the way we go out and apprehend drug users. Cops tend to go after drug people and execute drug warrants as if they are up against bank robbers, but more often than not, there aren't any guns. Yet here we were in full SWAT mode running around with no-knock warrants, endangering innocent parties in the home, children, roommates. When you look at the number of police killings, both the number of officers being killed and the number of people officers are killing have decreased, except when it comes to drug raids. Innocent people are being killed in drug raids because the informant is wrong, they hit the wrong house, the cops were too hyped-up and worried about their own protection. Our entire judicial district has taken a different stand: Now they are reluctant to give no-knock warrants because there were too many people killed, too many officers injured. Another example is the roadblocks in neighboring counties aimed at catching people coming and leaving the Telluride Bluegrass Festival. I don't do the roadblocks, it's a tactic I don't like using under any circumstances, except maybe if a desperado was on the loose. I don't even use checkpoints for drunk driving. I think it's un-American. And those checkpoints found very few drugs and made a lot of people angry. But a few years ago, I would have been out doing the same thing.

Q: What are the most important negative impacts of drug prohibition on law enforcement?

Masters: Corruption. The corruption not just of law enforcement but the entire criminal justice system, and not just in the sense of being bought off, but in that it seems the bottom line is you treat people differently depending on who they are. If you're the president's wife and have a drug problem, you get a clinic named after you. If you're poor or black or Hispanic, you languish in jail. It goes all the way from who gets stopped, to who gets prosecuted, to who goes to prison and who goes to rehab. It hasn't really hit the kids in suburbia or the kids of the rich. That is a tarnish on all of our badges. Then there is plain old corruption. There are a lot of people addicted to drug money and some of them are in law enforcement. The whole damn department in the county next door is involved in a meth ring, and I see those officers as victims of the system as well. One of them was a great officer, very friendly, he was busted, he [hanged] himself in jail last week awaiting transfer to the federal pen. One more victim of the whole American drug war culture. Yeah, he was a crooked cop, but he wouldn't have been if we didn't have this system.

Q: Do you make a distinction between drug use and abuse?

Masters: Absolutely. One of the problems with our existing laws is we make no distinction. The laws portray people who possess any drugs as criminals. But with legal drugs, such as alcohol, we set limits; we have a system with alcohol that maintains individual responsibility. That seems more sensible than making anyone who uses drugs or possesses drugs a criminal.

Q: Do you not fear an explosion of drug use if drugs were more easily available?

Masters: I always ask people who say that "Are you going to start taking them?" People who want drugs in America can go out and get them right now. This existing situation is the worst possible, the whole thing is driven underground and it's completely out of any sort of government or social control. We have to bring it above ground, away from the criminal element, and have an organized system to distribute it to adults that we will hold responsible for actions. That's what we do with alcohol and you don't see guys in trench coats down at the schoolyard trying to sell alcohol. I think we would have some people who have no self- control and that would be a problem, but we have that problem today.

Q: What would an ideal drug policy consist of? Opponents of reform always conjure up images of crack in vending machines.

Masters: No, that's what we have now. I want to see a regulated system of distribution done through the medical and pharmacological community for those people -- serious heroin or meth users -- who need the stuff, and that system needs to offer addicts some sort of rehabilitation. We've done this before; it worked well in the 1920s, before the federal government prevented doctors from prescribing morphine to addicts. Beyond that, marijuana should just be legalized, except you shouldn't be blowing dope in your car, or consume it in public. Same as alcohol. We don't allow people to walk around our town drinking liquor. I don't want my kids exposed to this stuff. That's why you have bars or your own home. I would concentrate law enforcement resources on things like driving under the influence, you have to keep that aspect of it. You can't be harming others.

Frazier Write-Up

Deborah Frazier wrote a December 10, 2001, article for the Rocky Mountain News titled, "Sheriff: U.S. drug policy a failure."

San Miguel County Sheriff Bill Masters is taking his war against drugs on the road.

"America's drug policy is a failure. We need to admit that and switch to a system of careful control," Masters said.

Masters, a Republican turned Libertarian, was elected in 1979 [actually appointed in 1980] in a county that includes Telluride.

"The plan is not to have heroin stores everywhere, but a system where people can clearly see all the drugs and know they don't need them," he said.

"The police and the politicians need to admit they've failed."

That's also the message in his book, Drug War Addiction: Notes From the Front Lines of America's No. 1 Policy Disaster, published by Accurate Press of St. Louis and due out this month.

The drug war, which reportedly costs every citizen $200 a year, has failed to curb gang warfare, drug-related murders and robberies, although half the inmates in federal prison are serving terms for drug offenses, he said.

"We are a drug culture. It's encouraged by ads for Prozac, Ritalin and Viagra," said Masters, who tries to avoid all drugs, but occasionally takes ibuprofen.

"I know that when I take something, it affects me."

Some drugs should be available, he said.

"Take medical marijuana. You have to be deathly ill from chemotherapy, suffering from cancer and lying on the bathroom floor vomiting and crying," he said.

"How can we be so cruel?"

For all the millions of dollars spent and thousands of people jailed, the same percentage of the population -- 1 percent -- is addicted to heroin and morphine today as were in 1900, Masters said.

"If people like drug killings, meth labs, overdoses, police corruption and drug-related crimes, then we have the perfect drug policy," he said.

"Thirty years ago, we had a little tiny drug problem.

"Now the quantity and quality are better, and it's all over the place." At his talks on the subject in western Colorado, the public has been supportive, Masters said.

"I've had people in their 80s drive hundreds of miles to my office after they heard me speak just to tell me they agree," Masters said.

DRCNet Notes

The Drug Reform Coordination Network posted the following report on its Web page.

San Miguel (Colorado) County Sheriff Bill Masters, author of the just published "Drug War Addiction: Notes From the Front Lines of America's #1 Policy Disaster," told DRCNet that the toll must also include the thousands of police officers killed trying to enforce US drug policy in countries such as Colombia and Mexico, as well as the innocent civilians caught in the crossfire. "Fortunately, the number of law officers killed in the US has dropped dramatically in the past 25 years," he said, "because of better tactics and better analysis of each law officer death. But the flip side is we don't do the same review on innocent people killed by police agents who raid the wrong house or shoot someone who committed no wrong," said Masters.

"The victims are not just police officers killed, but also innocent people killed and the police officers who have to live with the fact that they were put in a position to kill or be killed because of a failed policy," the long-time Colorado sheriff continued. "I really empathize with those officers who are put in that position by legislators and police administrators and who end up either getting hurt or hurting an innocent person. . . ."

Sheriff Masters echoed [Joseph] McNamara's comments. "These police officers are being trained with military tactics," he said, "but is this sort of tactic really necessary? Police will argue that the evidence could be destroyed without the element of surprise, but I'm not sure if a few grams of cocaine are worth an officer's life. Certainly not my officers," he said. "I won't put them in that position. It's a disaster waiting to happen."

Independent Interview

The Independent, the newspaper of Fort Lewis College in Durango, published the following interview with Sheriff Masters on September 28, 2001. Spencer Bath conducted the interview.

Indy: How long have you been involved in law enforcement?

I've been in law enforcement here in San Miguel County for 27 years now. I started out as a deputy marshal for the town of Telluride and then eventually became sheriff in 1980, and I have been the sheriff since then. I was a Libertarian back when the party formed in 1974 [the LP was officially formed in 1971], and then I switched and became a Republican when a position was open in the sheriffs office. I am a conservative. If I wasn't a Libertarian I'd be a conservative. I believe in limited government, that people should stay out of individual lives when it comes to what's going on in their bedroom, or in their homes, and certainly what they choose to put into their bodies. It's their right. It's a God given right, and I don't think anybody should be interfering with that. But I also hold people accountable for their actions. If people hurt others, or damage property, I don't want to hear any excuses, like, "I was drunk," or "I was stoned," that doesn't mean anything to me. I think if we approach [law enforcement] that way we would have a lot saner society.

Indy: Do your deputy sheriffs share some of the same opinions regarding drug enforcement?

Masters: It's interesting. Not all of them share my views on that; most officers believe the law is the law, and [they should] uphold the law. So I tell my officers. Don't be guessing what I would be unhappy with if you choose to enforce the law. But at the same time we have our priorities, and I direct them to those priorities; and they are crimes against people, secondly crimes against property, and crimes that may disturb the peace of the community. But the regulatory crimes, which many people call victimless crimes, or what I call a regulatory crime because [it is an attempt] to regulate a particular activity that there is no person complaining about... normally, it's two people consenting to do something: "I will give you marijuana for money," and we don't necessarily have a complaint that one or the other is violating the law. To me, those are laws that regulate peoples' behavior and I look on those as being low priorities for us to enforce. There are 30,000 laws in the state of Colorado, and there are only 12 deputies, so we have to triage the laws somehow. It's pretty ridiculous to [have this many] laws, and more and more it's just a vain attempt to control people's behavior, and we can't control that. Usually forces way beyond the law change peoples' behavior, and it has nothing to do with the law.

Indy: Do you find people involved in illicit drugs moving to Telluride because they sense some sort of tolerance there?

Masters: I certainly hope not, and that is one of the dangers of being a Libertarian sheriff, and that's what I tell my deputies, 'don't turn your back on this,' because I don't want people to show up because they think we tolerate this kind of behavior any more than we tolerate drunkenness, or drunk driving. We don't tolerate it. I don't want people coming here for that, but at the same time we're not going to be breaking down doors trying to bust people for marijuana. If you want to come here for the purpose of using drugs, my guess is you're going to run afoul of the law some other way. It's like a drunk moving to California for cheap wine. That person's got other problems that will come to the attention of the police.

Indy: Do your constituents support your views on the drug war?

Masters: I found a mixed bag. I found people that knew me for a long time and probably would have voted for me no matter what, and I found a tremendous number of young people that really appreciated the stance [that the drug war] isn't working, we don't want to be enslaved by an excess of taxes, we want opportunity. I wish the young people would stand up more for their rights as citizens. I don't know why young people don't stand up and say, "I won't vote for anybody that denies me the basic rights of citizenship." I think young people fail to recognize how powerful they are. If you listen to the politicians, there are a number of them who will use the lack of a [military] war, and they will make up some other war to get re-elected. The drug war is a great example of when we don't have an enemy. We did the same thing with the war on poverty, and that was another fiasco that we are still suffering from. Anytime a politician describes some kind of program like that, well you'd better look out.

Indy: Are you generally accepted by the law enforcement community despite your beliefs?

Masters: I guess the other sheriffs look at me as an oddity, but I am, I make no bones about it, but still, we are all cops and we all share a certain bond. They understand that I have a very strong difference of opinion, I am a civil libertarian, and I stand strongly for civil rights, but I've never been denied assistance from any law enforcement officer that I've ever called on. I also believe that a surprising number of officers, when they sit down and think about it, or after they get out of the business and look back at their career, have told me, "Bill, you're right. We have wasted so much time going after the wrong people, we've wasted our time going after these dope smokers when basically they were just young kids having a good time, and they weren't the criminals. We should have been going after the murderers, and the child molesters, and all these other people running around." Our whole country had better places to spend that $50 billion we spend yearly on the drug war. It's pretty evident to me that we have other priorities that we are ignoring.

Indy: Do you get any pressure from federal drug enforcement agencies?

Masters: I've never felt any pressure from a federal agency to change my viewpoints or do something different from what I'm doing. I've gotten into arguments with some of them but never have they not acted as professionals.

Indy: Many officers get defensive when you bring up the failures of the drug war, why?

Masters: If they are making their money off of [the drug war], if that is their livelihood, you might get some resistance. I think most officers feel they need to take a public face that says, "We are going to uphold the law." But in private many of them have the same viewpoints that I do, in that we have to change tactics. They all admit that it is not working, because drugs are everywhere, and so many of them say, "We need to have some other method of dealing with this because the law enforcement agencies are alienating too many people." We arrest 750,000 people every year for marijuana. More and more, [officers] are saying this is ridiculous, and we need to ignore that. We have too many other duties, too many other important things to do than worry about someone who wants to get stoned. My guess is it will change, and we will look back on these days like prohibition, and ask, "What were we thinking?"

Indy: How do you see laws changing?

Masters: Certainly [through] the states' rights movement on certain issues like medical marijuana. Personally, I don't understand how smoking something could be good for someone. I don't believe it, but if I was really sick and I thought that would help me, then it's my choice. I need to be able to make that choice. But when you see states beginning to defy these laws, whether you like it or not, the public is demanding the change. And usually when it comes to these kinds of things, the last people to change are the legislators. Long before a legislature decides to repeal a law, the people have already gotten to the point where they completely ignore it. Prohibition is a great example, everybody was as drunk as skunks. They are usually the last ones to react. But it is also going to be a fight, as we come to the end of any war, it becomes more difficult and more dangerous for both sides, and I think we are in that point right now.

Indy: Do you have personal experience with police corruption due to illicit drugs?

Masters: Unfortunately I have. I've been very close to some of it. The recent case in Ouray County is probably the worst I've seen in quite some time, where a couple of officers were involved in methamphetamine dealing. A lot of them are going to do a lot of time in jail, because not only were they dealing dope, they were using their firearms, their police cars, to guard this dope. And here was a little, good-old-boy, dope dealing sheriff's office.

Indy: Is it all in the interest of money?

Masters: As Glenn Frey says in "Smugglers Blues," "It's the lure of easy money/ It has a very strong appeal." You know it was the money, power, sex with women strung out on the dope, it was a terrible case of police corruption. And we don't get much press but it was right here in rural western Colorado. When I started this business it was a little bit of dope in the inner cities of America, and now it is everywhere; obviously we are doing something very, very wrong in fighting this battle and anybody that claims differently is a fool. I don't think there is anyone who knows that these [Ouray] officers were going in and executing search warrants and screwing the women who were there. Its unbelievable to me. It's a noble profession, and it needs to be maintained that way but the drugs have such a corrupting influence, just because of their illegality, and it has corrupted the entire system, all the way up and down the chain. Any vice-related thing, you're going to have those types of instances occurring; or where you have a perceived societal wrong that the police are trying to solve, it becomes ripe for corruption. It's upsetting that these types of things occur right here in rural Colorado. And to me that's more newsworthy because you can almost understand that it happens in big cities, but when it reaches out this far, you know that it has affected every corner of America.

Indy: How about excessive use of force?

Masters: Some of these issues with some of these police shootings, as with Mena in Denver, and in the officer's zeal to enforce the drug laws, the officer lies, and falsifies an affadavit in order to get in and bust these people, and it turns out to be the wrong address and this fellow gets killed by the SWAT team, because the officer is a zealot to the drug war. And the sad part about it is that I understand where that officer is coming from, because he thinks he is saving his community. He thinks he is justified.

Indy: Many liberals criticize the drug war, but they would simply replace criminalization with government mandated treatment, do you think it should be left to individuals to address their own problem entirely?

Masters: Well no matter what, an individual needs to take responsibility for his actions completely. It's your problem, and we don't want any grants, we don't want anyone paying for your treatment, because that's part of your treatment, that you accept responsibility and you have to pay for it. The taxpayers should get out of the [treatment] business. They need to say, "These people are going to pay for their treatment." People who are disabled by drugs or alcohol are at the point where they are incapable of carrying forth themselves and are a danger to themselves or to others. The government, or society, has to step in and discipline these people. Otherwise they're just going to be in the gutter, and communities aren't going to tolerate that. They can't have people in downtown Durango lying in the gutter, drunk. When they're incapacitated by drugs or alcohol, we should intervene. But just because someone possesses drugs, or has some with him, to say "He needs treatment," now I disagree with that. That person may not need treatment, and I don't think the government should demand that. And you look upon some of the liberals, they believe the government should get involved in every bit of your life, and we hear this all the time with domestic violence cases. People are animals, and when we visit a domestic violence scene, liberals say, "You have to intervene," mainly in the woman's life, and tell her, "Listen you're so stupid, you can't figure it out, you need to get away from this clown, and so were going to force you, we're going to make you testify against him." Then you have lost your right to say, "No, I'm going to handle it my own way." And [the liberals] would do the same thing to the person who is using drugs, and say, "You have lost your right to direct your life and we're going to put you in a treatment center." Once again, the people who are disabled or incapacitated by drugs or alcohol, we have to intervene, but everyone else should make the decision for themselves when they need treatment. Unfortunately the criminal justice system allows peoples' addictions to be used as an excuse for their behavior, and that's wrong.

Indy: How do you feel about asset forfeiture? Do you see law enforcement confiscating property in order to benefit their own department?

Masters: I've seized people's homes, and we act like a bunch of damn pirates; we sit around the table and split up the money, or the booty, and I think this asset forfeiture is fascist, like the Nazis coming down on people and seizing their property, especially when it does not involve a conviction, and sometimes the government uses the civil forfeiture laws because you only need a preponderance of the evidence; you don't need reasonable doubt. All you need is 51 percent of the proof, so, in civil law, it's easy to seize peoples' homes. I would say I'm against that except after there is a conviction and we can clearly tie those assets to a criminal activity. But once again, most of these [asset forfeitures] involve regulatory crimes. When it comes to someone who has amassed money consentually, or people gave them the money because they had the product they wanted, well I'm not sure that seizing people's homes is the best thing to do. And it all depends on a matter of degree; I think initially they thought, "Well, here are these huge Colombian drug dealers with these multi-million dollar homes, screw them, they're making their money off people's misery." But what has happened is we are now seizing poor people's homes, and poor people's cars, and these people don't have the money to fight that. The Colombians don't care, but the poor people who have a little bit of marijuana in their car, and they lose it, man I feel for those people. And so I think the whole process has gone too far.

LP News Review

Jonathan Trager wrote a review of Drug War Addiction for LP News, titled, "Kicking the addiction."

"When reformers point to the flaws and problems of the drug war, the warriors' answer is to do more of it.

"Isn't that the response of all addicts?"

So asks Bill Masters in his new book, Drug War Addiction. In this work, Masters charges that contemporary Drug Warriors are themselves addicted to waging an unwinnable war -- while ignoring its assault on the liberty, privacy, and safety of peaceful American citizens.

The book is actually a compilation of essays Masters has written on the Drug War over the years. Throughout, Masters offers readers some of the wisdom he has gained during his 22-year career as the sheriff of San Miguel County, Colorado, about what he calls "America's #1 Policy Disaster."

A one-time Drug Warrior -- he even received an award early in his career from the Drug Enforcement Administration for "outstanding achievements in the field of drug law enforcement" -- Masters explains in riveting detail his motivation for eventually becoming one of the war's most vocal opponents. For example, Masters views the militarization of local police forces as a dangerous result of enforcing drug prohibition.

Did you know that between 1995 and 1997, local police forces across America obtained from the military 3,800 M16 fully automatic assault rifles, 73 M79 grenade launchers, and 112 armored personnel carriers, largely for purposes of fighting the Drug War?

I didn't -- and I feel more than a little uncomfortable knowing that local police forces have the firepower of a small army. I mean, grenade launchers? Give me a break.

Masters is also dismayed that the Drug War has negatively affected how police officers -- whom he calls "peace officers" -- have come to be viewed by many Americans. Instead of being considered as friends and protectors, argues Masters, officers are frequently regarded with suspicion and fear.

"The rift drug prohibition has created between the police and the public is one of the saddest results of our policies," he writes. "Peace officers across the nation feel in their hearts that something is amiss, and I believe more and more of them are realizing just how insidious prohibition really is."

Masters also devotes a chapter to addressing objections readers might have to ending the Drug War, such as the argument that legalizing drugs would "send the wrong message" to America's youth. A self-described "spiritual man," Masters takes issue with social conservatives who attempt to equate the Drug War -- and the law in general -- with moral righteousness. "Morality isn't the same thing as the law," Masters writes. "The law touches on only limited aspects of morality: protecting people and their property from physical harm and preventing theft and fraud. Morality is broader than the law. When we try to make the law as big as morality, laws become profuse, ambiguous, unknowable, flaunted, and unenforceable."

Instead of trying to find "external solutions" to spiritual problems, he argues, Americans must try a new approach that addresses the root cause of drug abuse: The conviction that happiness is a state of mind divorced from a person's action and character.

My favorite part of the book was definitely the final chapter, "Simple Laws: Pathway to Freedom." Here, Masters discusses the "core belief of the Libertarian movement" -- personal responsibility.

"We must not abdicate our responsibility and surrender it to the government," he writes. "It is our responsibility to deal with such issues as health care, our retirement, raising and educating our children, the defense of our homes and families, our domestic relations, and our own alcohol or drug abuse. If we fail to take responsibility for our own lives, we can blame only ourselves when the government takes away our liberty to determine how those issues will be addressed."

Although Masters is humble about his writing ability, I was pleasantly surprised by his natural style. Each chapter had a simplicity and clarity that made the book a pleasure to read.

In addition, Masters' personal Drug War horror stories are intriguing, and there are interesting Drug War quotes from well-known personalities on every page, from former president Abraham Lincoln to popular musician Dave Matthews.

One improvement would have been to focus exclusively on the War on Drugs -- as opposed to issues such as gun control, which Masters tries to briefly address -- which would have helped keep his message more concentrated and powerful.

But at a mere 135 pages (including three appendices), this book is certainly a welcome addition to a growing cornucopia of anti-Drug War literature. Maybe, if enough people read thoughtful and well-written books such as this one, America will finally find the courage to kick its Drug War Addiction.

LP News Article

LP News published an article titled, "War on Drugs threatens America, says Colorado Sheriff Bill Masters."

The War on Drugs is a tragic waste of resources that makes Americans more vulnerable to vicious criminals and bloodthirsty terrorists -- while it simultaneously "tarnishes the badge" of law enforcement.

That was the blunt message delivered in the Keynote Address by Sheriff Bill Masters to delegates at the Libertarian National Convention in Indianapolis, Indiana on July 5 [2002].

"We've tried it. It doesn't work," said Masters about the War on Drugs. "But we're not supposed to question a policy that funnels millions -- probably billions -- into the hands of punks, criminals, and terrorists."

In a speech repeatedly punctuated by applause, Masters, the chief law enforcement officer in San Miguel County, Colorado, charted his course from pro-Drug War zealot to high-profile dissident who dared question the "emperor's new clothes."

When he was first elected sheriff in Telluride 23 years ago, the small Rocky Mountain town was a "blue-collar community of hard-rock miners" where the chief law enforcement problems were "a few drunks and a few fights," said Masters.

One time, when he had to face down a gang of street toughs, townspeople rallied behind him because they considered themselves the "sheriff's back-up," he said.

However, as Telluride transformed itself into a popular ski resort, drugs like marijuana and cocaine started showing up in increasing quantities, and the sheriff enthusiastically jumped into the War on Drugs.

"I took the [drug] laws seriously," said Masters. "We started arresting more and more people for small amounts of marijuana. We arrested businessmen, high school kids, housewives, and the editor of the local newspaper."

The rapidly expanding sheriff's office arrested so many people that it had to rent jail space in a neighboring county to house all the prisoners, he said. During those years, Masters said he would "play the tough guy" to get more anti-drug funding from the city council -- and used the money to hire more officers and dispatchers, and buy more cars and other equipment.

"I was the tough guy on the easy [criminals] -- the dopers," he said. "Busting these people isn't rocket science. It's easy."

As the San Miguel County War on Drugs escalated, and a broader swathe of citizens were arrested, the relationship between the townspeople and the sheriff's office cooled, said Masters.

Citizens who once stood proudly "behind me now hung me in effigy," he said. However, two events finally caused Masters to reconsider his views on the War on Drugs.

The first was when a brutal serial killer kidnapped a local woman. Masters turned to the FBI to help, and visited the agency's training center in Virginia.

There, he was shocked to see a mere handful of FBI agents assigned to kidnapping cases, with papers piled high on their desks, he said. Meanwhile, hundreds of new DEA agents were being trained to fight the War on Drugs, so they could arrest people for smoking marijuana.

Later, back in Telluride, a newly arrested drug dealer told Masters, "Every time you bust someone [for drugs], my risk, my price, and my profits go up."

"He could have taught economics at high school," said Masters ruefully. And another dealer told Masters: "Sheriff, maybe you're trying to shove hay into the wrong end of the horse."

"Sometimes you need to hear that," said Masters.

At that point, Masters said, "I realized that our priorities were all wrong. I had failed my community by not analyzing the drug problem. I had directed our precious law enforcement resources in the wrong place."

After September 11, Masters said he had another revelation: That the War on Drugs makes America more vulnerable to such terrorist attacks.

"The year before September 11, the United States arrested 700,000 people for drugs ... and one suspected terrorist," he said. "I don't like those numbers."

And while the FBI said it lacked the resources to check out reports of suspicious foreigners taking "kamikaze flying lessons" at flight schools, it had the resources to arrest "three-quarters of a million Americans for possessing a harmless plant," he said.

The War on Drugs also threatens Americans in another way, said Masters: Through heavily armed, overzealous law enforcement. Solemnly reciting the names of innocent Americans who were accidentally killed by police during anti-drug operations, Masters said, "The list goes on and on -- old people, children, and businessmen -- shot and killed during drug raids by those sworn to protect us."

And finally, the War on Drugs also unfairly targets the poor and minorities, said Masters.

"Some people languish in jail for years on drug charges, while others will get a drug rehab clinic in California named after them," he said.

Instead of continuing a harmful policy that "tarnishes the badges" of law enforcement, Americans should follow the lead of Libertarians, and end the War on Drugs, concluded Masters.

"Upholding liberty must be the priority of laws in a free society," he said.

Drawing the Line

On June 2, 2004, Reggie Rivers hosted a discussion about The New Prohibition for his Channel 12 KBDI television show, Drawing the Line. Ari Armstrong, who served as assistant editor for the book, appeared in studio, along with contributor Dave Kopel. On the other side were U.S. Attorney John Suthers and Mark Pautler, Chief Deputy District Attorney for Jefferson County. Sheriff Bill Masters and Judge John Kane, another contributor to the book, participated in the show via telephone.

Lady Liberty Interview

Following is Lady Liberty's review and interview with Masters.

The New Prohibition isn't the first book to criticize American drug policy and the so-called War on Drugs. In fact, Sheriff Masters has himself written on the topic before. What sets The New Prohibition apart isn't its subject matter nor the fact it's a collection of essays. No, what makes The New Prohibition different and gives it maximum impact is that its viewpoints come from so many different-and authoritative-directions.

Worried about the rule of law? There are several essays written by law enforcement officers, both active and retired. Likening the Drug War to the spectacularly unsuccessful prohibition on alcohol, the writers show in terms of personal experience and knowledge the extreme violence and other criminal behaviors engendered by prohibition eighty years ago and by the War on Drugs now.

What about public health? Doctors and administrators write against the present drug police from their own perspectives. Not least of their concerns is compassion for the ailing (which some states are beginning to recognize, but which the federal government still blithely and cruelly denies). Social implications, too, are considered and found to suffer under current policy as well.

Politicians discuss in writing the changes that must be made to the system; a judge and several attorneys weigh in on the overburdened court system and irrationality of sentencing guidelines. And then the argument is taken beyond our own city streets and the Fourth Amendment. Though you may not have considered it, The New Prohibition will show you how the War on Drugs also affects the Second and Tenth Amendments and even foreign policy. Of course, the book couldn't be complete if the claims that illicit drug use helps fund terrorism weren't also addressed.

Whatever your own argument against the War on Drugs, it's bolstered here. And if you're in favor of the War on Drugs, you won't be when you've finished The New Prohibition. There are simply too many very good reasons you shouldn't support the War, and they're presented so cogently here you'll find them impossible to ignore.

Although the foreword of the book is short, it strikes me as a particularly appropriate choice to let the introduction be by former Minnesota Governor Jesse Ventura. When Jesse Ventura ran for state office, he was very much a third party underdog. He didn't have the organization or the money that the two major parties did. And yet he appealed to the people, and they voted accordingly. In much the same way, the War on Drugs has an almost bottomless financial well to draw from while it enjoys a substantial enforcement infrastructure.

But many people are beginning to see the flaws in the system, and it's entirely possible that the status quo will be upset in the near future. Books like The New Prohibition will help that day come sooner, and for all of those who've been victimized in any of a multitude of ways by the War on Drugs, that day can't come soon enough.

LADY LIBERTY'S READ: I've long found the War on Drugs to be irrational purely from a prohibition standpoint. So certainly I felt vindicated when I read some of what was contained in The New Prohibition. While that's nice, the best parts of the book came for me when I found such well-reasoned arguments from other perspectives, some of which I frankly hadn't even considered.

If you want to know more about the pitfalls of the War on Drugs, I can't imagine a more complete or reader friendly book for you to use to start-or complete-your education. But be warned: finding so many other reasons to oppose the War on Drugs made me angrier than ever at those who perpetuate it. Still, if that anger can serve as motivation for change, then here's hoping it makes you mad, too.

Interview with Bill Masters

Colorado Sheriff Bill Masters is on a crusade. Of course, he does his job working to protect the citizens of his county and arresting the bad guys there. But his greatest passion is reserved for righting what he sees as a truly great wrong, and that wrong is the so-called War on Drugs.

There's little question that Masters is fighting on the right side despite the seeming incongruancy of a law enforcement officer coming out against the War on Drugs. But he's seen firsthand, and heard stories directly from others with similar experiences, just how little good and how much evil the existing drug prohibition in this country has done. Any law enforcement officer who takes seriously his oath to protect "civilians" can't ignore insensible statutes; inconsistent enforcement; draconian penalties all too frequently unfairly applied; the temptations for abuse of authority; and the massive waves of crime and violence encouraged and abetted under prohibition. And Masters doesn't. Instead, he works toward sorely needed reform.

Sheriff Masters was once an uncompromising enforcer of drug laws. In fact, he won an award for being so good at it. But in the face of evidence that showed him the War on Drugs was more of a problem than the drugs themselves, and his notion that there are better ways to deal with those drug problems not actually caused by enforcement activities, he determined that repeals and reforms were the only logical way to proceed. Several years ago, he wrote a book entitled Drug War Addiction. In that book, he revealed much of what he'd learned about the War on Drugs over his years in law enforcement, and he offered his own ideas for ways to address both drug use and drug enforcement in a more efficient, effective, and rational way.

Masters has now published The New Prohibition: Voices of Dissent Challenge the Drug War. This book consists of a collection of essays all discussing and dissecting the American War on Drugs. Masters wrote one of the included essays himself, and serves as the editor for the rest. The New Prohibition isn't the first book to criticize American drug policy and the War on Drugs. But what sets The New Prohibition apart isn't its subject matter nor the fact it's a collection of essays. No, what makes The New Prohibition different and gives it maximum impact is that its viewpoints come from so many different-and authoritative-directions.

After having read both books, I had a few questions for Sheriff Masters which he kindly took the time to address.

Lady Liberty: I've heard it said in the past that law enforcement officers take an oath to uphold the law. It doesn't matter whether they like a particular law or not, they must enforce it. Is that true?

Sherriff Bill Masters: Police officers have a tremendous amount of discretion in the enforcement of law. Few laws (some domestic violence laws, etc.) actually require that law enforcement officers make arrests. 90 percent of a good police officer's activities involve resolving problems without the application of legal processes.

LL: I'm not the only person that has suggested that law enforcement officers simply refuse to enforce a law that's just plain wrong, much as I would advocate juries to take advantage of their powers of jury nullification. Is that what you did in connection with the various laws that make up the War on Drugs?

SBM: No. We, the sheriff's office, do not refuse to enforce any law. There may come a time when the application of the law is the best answer to a problem. Really bad laws are recognized as such only after the police apply the letter of the law to the issue. If the police arrested everyone-not just kids and black people but prescription pill popping and pill sharing housewives, Jeb Bush's ("just a private family matter") daughter, Rush Limbaugh etc.-who violated any drug law, "normal people" (white voters) would demand change. Just like other wars, change doesn't really happen until middle American kids are coming home in body bags with no end in sight.

LL: I trust your decision-making abilities. I've read your books, and you're obviously interested in constitutionality and in what I'd call libertarian logic. But what about those in law enforcement who can't be trusted?

SBM: Listen, the problem is not with law enforcement being trusted. They are just doing what the legislative branch tells them to do and funds them to do. Put the blame on the senators and congressmen who are "states' rights, small federal government" talkers [but who] then vote to fund federal drug enforcement on all levels. Put them on the discussion panels, not the cops.

LL: You determined some time ago that the War on Drugs was wrong. Did you change your attitude suddenly, or was it a gradual shift? What was the "straw that broke the camel's back" so to speak that tipped you to the other side in the War on Drugs?

SBM: I really always felt this way. I just forgot to listen to logic and my true conservative (limited government/personal responsibility) roots. The straw for me was the misallocation of law enforcement dollars away from homicide investigations and now terrorism prevention and into busting pot smokers.

LL: Did you debate the matter with your colleagues?

SBM: Most cops don't debate the law. The ones that do, besides the political hacks, know that change is needed.

LL: Once you made your decision, what was the reaction of your colleagues? How about that of your superiors?

SBM: I am an elected official, so I have no superior other then the public I serve. Most of my colleagues thought I was crazy or a drug user. Most now are beginning to understand that change is in the air. Some even say that the drug war is over.

LL: Many people are convinced that the War on Drugs is bad, or at least unwinnable. The federal government, however, has made it clear that it disagrees. How can local and state authorities overcome the threat implicit in that fact?

SBM: Don't make it a liberal issue; make it a conservative one. It is, pure and simple, a nanny state-big federal government, wasteful spending, no states' rights issues. True Democrats should love it, and true Republicans should hate it.

LL: Obviously, if you had a magic wand, you'd wave it and make a few changes. If you could literally rewrite American drug policy overnight, what would it look like tomorrow morning? SBM: 1. States decide the drug laws that are best for them; 2. People have a constitutional right to decide what goes into their bodies; 3. People, not objects, are judged harshly for their actions that directly hurt or endanger others.

LL conclusion: It's cynical to say so, but I also suspect it's all too true that Sheriff Masters' suggestions make too much sense for the authorities to suddenly adopt. Too many agencies have become dependent on the money they get from forfeitures based on drugs or the accusations of drugs (something Masters addresses in his book Drug War Addiction). At least as many have also become enamored with their own authority. But at least we do know that, when the time comes, there are people ready with cogent alternatives to the War on Drugs. We can only hope that it won't, as Masters puts it, take too many more American kids in body bags to initiate the needed changes.

My thanks go out to Sheriff Masters first and foremost for his thought-provoking books, and for taking the time to talk about his views.