Ari Armstrong's Web Log (Main) | Archives | Terms of Use

Reclaiming Liberalism and Other Essays on Personal and Economic Freedom

This book originally was published in 2016. I published this html version of the book at AriArmstrong.com on December 14, 2025. I retain the copyright. No part of this book may be reproduced elsewhere without my explicit permission. If you wish to help financially support this work, please purchase a paperback or ebook through Amazon, join my Patreon, or donate through PayPal. Historical note: In the years since this book was published, the major threat to liberty in the United States has become Donald Trump's MAGA movement. Also, I've read the work of Matt Zwolinski and John Tomasi on libertarianism, and it raises important questions about claims of property rights in some contexts and about welfare spending. So, while many of my views have remained stable, I'm not as sure of some of my conclusions as I once was. Thank you for reading, —Ari Armstrong

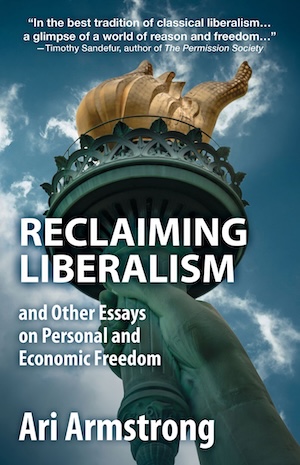

In the best tradition of classical liberalism . . . a glimpse of a world of reason and freedom. . . ." —Timothy Sandefur, author of The Permission Society

Reclaiming Liberalism and Other Essays on Personal and Economic Freedom

Ari Armstrong

Ember Publishing

Denver, Colorado

Copyright © 2016 by Ari Armstrong

Includes Index

Political Theory, Government, Current Affairs

Designed by Jennifer Armstrong

ISBN: 978-0-9818030-2-9 [paperback]

For Tomorrow’s Liberals

Contents

- Liberalism Pertains to Liberty

- The Incoherence of Conservatism

- Conservatism, Utopianism, and Liberalism

- Liberalism as Radical and Rational

- The Problem with Left and Right

- The Long-Term Reclamation of Liberalism

- Why Not Libertarianism?

- Renewing the Fight for Liberty

2. Utopia and Totalitarianism

3. Liberty and Equality

- “You Didn’t Build That”—Obama’s Ode to Envy

- The Justice of Income Inequality Under Capitalism

- Egalitarianism versus Rational Morality on Income Inequality

- Challenging the Inequality Narrative

- An Aristotelian Account of Responsibility and Luck

- A Parable for Thomas Piketty

4. Capitalism

- Contra Occupiers, Profits Embody Justice

- Sparking a Free Market Revolution

- The Fruits of Capitalism Are All Around Us

5. Freedom of Speech

- A Lesson on Censorship

- When Politics Corrupts Money

- Why Forcibly Limiting Campaign Spending is Censorship

- The Egalitarian Assault on Free Speech

- Campaign Laws Throw Common Sense Out the Window

- Ruling Furthers Free Speech

6. Welfare and Taxes

- Questioning the Welfare State

- The Integrity of Condemning Social Security While Collecting It

- Nation Needs Shared Liberty, Not Sacrifice

- The Crucial Distinction Between Subsidies and Tax Cuts

7. Liberty for Producers

- The Moral Case Against Minimum Wage Laws

- The Morality of Unequal Pay for Unequal Work

- Hobby Lobby and Equal Rights

- On the Right Not to Bake a Cake

- Businessmen Should Never “Put Moral Judgments Aside”

- Religious Freedom Laws vs. Equal Protection of Rights

8. Immigration

9. The Nanny State

- Government Destroys Buckyballs, Assaults the Mind

- Should Prostitution Be legal?

- Morality and Sanity Demand an End to Drug Prohibition

[11]

Reclaiming Liberalism

My aim is to reclaim the mantle of liberalism for those who advocate personal and economic freedom, individual rights, and constitutional government that protects rights. This implies that I think there is something amiss with how most Americans today describe themselves politically. We begin there.

What is a conservative? What is a liberal? For most Americans, those labels (among others) adhere to different packages of beliefs.

A conservative, by the usual way of thinking, is someone who leans toward an originalist interpretation of the Constitution; supports relatively free markets, albeit with some trade restrictions and welfare; embraces Judeo-Christian religion; opposes abortion; and accepts a variety of restraints on personal behavior, such as prohibitions of various drugs.

A liberal, by contrast, supports a “living” and malleable Constitution; calls for extensive government regulation of the economy and for large-scale wealth transfers; embraces secular government, with a legal wall separating church and state; favors legal abortion; and accepts a somewhat different set of restraints on personal behavior, such as gun restrictions and “sin” taxes on tobacco and soda.

Conservative thought leaders, Republican candidates, and their fans often spit the word “liberal” as an indictment. Liberal views are what’s wrong with the world, and liberals are despicable [12] for promoting those views, goes the line. Liberalism turns “good men into whiners, weenies, and whimps”; it is a “sin” and a “mental disorder” leading to the “demise of America” (to borrow from various book titles). Right-thinking people are not liberals; they are conservatives. Liberalism and conservatism are opposite ends of the political spectrum—corresponding to the political left and right—with moderates in the middle.

Meanwhile, those on the political left (or so regarded today) are happy to embrace the term liberal to describe their views, which they see as corresponding with the so-called Progressivism of the democratic socialist tradition. They, too, see liberals and conservatives as inhabiting opposite ends of the political spectrum, although left-liberals tend to call their opponents “right-wing extremists” and the like. For whatever reason, “conservative” doesn’t seem to be as dirty a word for those on today’s left as “liberal” is for those on today’s right—but conservatism still is eyed with suspicion and disdain.

The problem with such labels as conservative and liberal as typically used is that they group people very roughly by demographic similarities, not by logical coherence of beliefs about ideology and policy.

For example, why do conservatives tend to favor prohibitions of drugs but not of guns? The answer comes mainly not from logic but from anthropology. Conservatives tend to be rural, where rates of gun ownership and hunting are high and where police are distant; and they tend to embrace more fundamentalist sorts of religion, which condemn drunkenness and the like.

On the other hand, why do today’s American liberals tend to favor prohibitions of guns but not (always) of drugs? They tend to be more urban, where fewer people legally own guns or hunt. Many urban areas have relatively high rates of violent crime, and the police usually are faster to respond to emergencies. What about drugs? Recall that alcohol Prohibition was a Progressive cause. But today’s liberals often focus on the police and incarceration abuses fostered by the drug war. And they tend to be younger and more open to personal experimentation with drugs and the like.

The labels conservative and liberal can be useful in an anthropological consideration of political demographics—particularly as so many Americans self-identify using those terms. The problems come when people mistake anthropological labels for conceptual tools to understand political philosophy.

[13] For many people, the terms conservative and liberal become a cover for intellectual laziness. It’s just “obvious” that conservatives believe one set of things while liberals believe another, so why worry much about whether it makes any sense to embrace the elements of a particular package of beliefs?

People who embrace one of today’s usual packages of political beliefs often engage in ad hoc rationalization rather than genuine reasoning about those beliefs. For example, self-described conservatives tend to embrace the ideal of self-responsibility—why, then, do many conservatives argue that adults are responsible enough to own an unregistered AR-15 semi-automatic rifle with thirty-round magazines but not to smoke marijuana? Perhaps the conservative would answer that smoking marijuana can reduce a person’s capacity for self-responsible action. Well, so can drinking alcohol—and yet hardly any conservative argues for the return of alcohol prohibition. At the same time, many self-described liberals care about the problems of police abuses and needless incarceration caused by drug restrictions while ignoring such problems when caused by gun restrictions—probably because relatively few or their friends and political allies own guns (or at least “scarier” guns).

People who come up with arguments piecemeal to prop up the various elements of their package of beliefs—usually the package that their family or friends embrace—rarely think about whether the elements of the package fit together into a logically coherent whole or about the deeper philosophic grounding of their beliefs.

So why don’t we just relegate such terms as conservative and liberal to their anthropological uses and come up with a different set of terms for political philosophy? The answer is that the term liberal, by historical use and by etymological development, is well suited for use as a concept of political philosophy. “Liberal” should mean not only the package of beliefs widely embraced [14] by the self-described liberals of a given era; it should refer to a philosophic worldview that logically implies certain beliefs and policies and not others. As we will see, “conservative” is badly suited to describe a particular political philosophy; nevertheless, we do well to seek a clear, conceptual understanding of the term. The proper goal is to clarify the meaning of the terms liberal and conservative (among others); concocting new terms would increase confusion rather than reduce it.

To think straight we need clear concepts. So let’s begin to untangle the meaning and implications of the common terms we use to discuss politics, beginning with liberalism.

Liberalism Pertains to Liberty

Today in America, many people who call themselves liberals openly endorse censorship of political speech; civilian disarmament by bureaucratic fiat; pervasive violations of freedom of contract, especially involving work; part-time involuntary servitude for the sake of “redistributing” wealth; forced service by business owners for purposes of which they ideologically disapprove; the substantial takeover of education from pre-kindergarten to college by the national government; and a host of other authoritarian measures.

Such people and such policies are not liberal; they are anti-liberal. To effectively advance their cause, true liberals—people who in fact advocate liberty in all affairs, personal and economic—must reclaim the mantle of liberalism. The authoritarians, the statists, the collectivists who stole the term liberalism from its rightful heirs must be stripped of their rhetorical masks and exposed for what they are: enemies of human freedom.

The call to restore liberalism to its historically and etymologically soundest meaning is hardly new. The great liberal (free-market) Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises, before fleeing the Nazis and bringing Carl Menger’s school of economics to New York, wrote the book Liberalismus—later translated as [15] Liberalism—in 1927.1 In 1966, Mises discussed his use of the term liberal in his book Human Action:

I employ the term “liberal” in the sense attached to it everywhere in the nineteenth century and still today in countries of continental Europe. This usage is imperative because there is simply no other term available to signify the great political and intellectual movement that substituted free enterprise and the market economy for the precapitalistic methods of production; constitutional representative government for the absolutism of kings or oligarchies; and freedom of all individuals from slavery, serfdom, and other forms of bondage.2

Similarly, the Chicago economist Milton Friedman (with whom Mises had important disagreements) embraced the term “liberal,” although as a matter of convenience rather than as an “imperative.” He writes:

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, an intellectual movement developed that went under the name of Liberalism. This development, which was a reaction against the authoritarian elements in the prior society, emphasized freedom as the ultimate goal and the individual as the ultimate entity in the society. It supported laissez faire at home as a means of reducing the role of the state in economic affairs and thereby avoiding interfering with the individual; it supported free trade abroad as a means of linking the nations of the world together peacefully and democratically. In political matters, it supported [16] the development of representative government and of parliamentary institutions, reduction in the arbitrary power of the state, and protection of the civil freedoms of individuals.3

However, in the 20th Century, Friedman continues, the term “liberal” began to mean advocacy for coercive transfers of wealth (“welfare”) and government intervention in people’s affairs to achieve such transfers. Friedman continues:

This use of the term liberalism in these two quite different senses renders it difficult to have a convenient label for the principles I shall be talking about. I shall resolve these difficulties by using the word liberalism in its original sense. Liberalism of what I have called the 20th century variety has by now become orthodox and indeed reactionary. Consequently, the views I shall present might equally be entitled, under current conditions, the “new liberalism,” a more attractive designation than “nineteenth century liberalism.”

Liberalism is best understood to mean devotion to and advocacy of human liberty. Today’s true champions of liberty and true heirs of the liberal tradition need to put an end to the widespread perversion of the term by the anti-liberals who now claim it.

Advocates of liberty should reclaim liberalism for three basic reasons.

First, historically, the term liberal in a political context most prominently describes the broad movement that, in the main, advocates freedom in economic and personal affairs, grounded in [17] a (broadly) Lockean theory of individual rights and representative government.

Second, etymologically, the term liberal relates to being free or unbridled.4 True, “liberal” can also refer to generosity (roughly, free in offering aid) and freedom from prejudice. But these alternate meanings do not buttress today’s authoritarian “liberalism.” Generously spending one’s own resources is hardly on par with generously spending the resources of others. Presuming that elements of economic liberty arose from prejudicial beliefs is to begin with one’s conclusions rather than to prove them. I would argue that liberalism, in the sense of freedom in economic and personal affairs, encompasses consensual generosity and overturns the prejudices of humankind’s authoritarian past.

Third, by appropriating the term liberal, the authoritarians left the advocates of (broadly) Lockean liberty (“free minds and free markets,” as Reason magazine summarizes it) without a good term of their own. It’s not as though these statists needed another term: They already appropriated “socialism” to mean social coercion and “Progressivism” to mean (democratic) socialism—which genuine liberals regard as deeply regressive. Neither the term conservative nor libertarian aptly describes the ideological movement properly called liberal (for reasons considered below). By allowing statists to co-opt the term liberal, liberals of the Lockean tradition largely erased themselves from modern discourse. People have a hard time thinking about that for which they lack a good conceptual term.

Today, the most “obvious” alternative to statist “liberalism” is conservatism. But, not only is today’s conservatism often at odds with (Lockean) liberalism, it is not even a coherent political philosophy in its own right. Let us take a closer look.

[18]

The Incoherence of Conservatism

As an ideology, conservatism ultimately is incoherent. Conservatism makes sense only with respect to a particular and specified historical tradition; to oppose any and all change as an end in itself is to embrace stupidity, not an ideology. A delimited conservatism necessarily sanctions the ideological roots of the tradition it seeks to conserve; hence, conservatism is not an ideology, but rather a commitment to some particular ideology implied by or manifest in some tradition. So a conservative, depending on particulars, might favor monarchic rule over revolution, American constitutionalism over “living constitution” Progressivism, slavery over abolition, or religious tradition over secularization (as a few examples).

Conservatism cannot be salvaged as a coherent ideology in its own right by taking it to mean favoring “institutions and practices that have evolved gradually and are manifestations of continuity and stability” (as the Encyclopaedia Britannica has it).5 Such an interpretation has two basic problems.

First, in almost all places and times, multiple traditions coexist, so to conserve one line of tradition often means to rebel against another. So, for example, when the tradition of slavery butts heads against the (newer) tradition of individual rights, which shall the conservative conserve? In many cases, conservatism is but an intellectually sloppy way to rationalize the embrace of one tradition over another while leaving deeper reasons or motivations shrouded. The attitude often seems to be, “What reasons need I? I’m a conservative.” By the same token, one who looks hard enough can place any proposed change within the boundaries of some tradition or other, often going back to the ancient Greeks or further. Both the Nazis and their enemies could claim the conservative mantle, as could both the slavers and the abolitionists.

[19] Second, there is no such thing as consistently gradual evolution of human institutions over sufficiently long periods of time, so conservatives necessarily embrace whatever radical changes transpired in the tradition they seek to uphold. Do Christian conservatives deny that their religion was at its founding radical, and that its widespread embrace led to profound and relatively fast social change? Do Constitutionalists deny that the American Revolution was a radical response to monarchic abuse, resulting in far-reaching social upheaval? Scratch a conservative, find a revolutionary—if you take a given tradition back far enough.

To continue this last point, one problem with conservatism is that any revolutionary can claim to be a conservative; there is no change so dramatic that its defenders can’t frame it neatly within some tradition. By any sensible reading, Christianity is radically different from the religion of the Torah. Yet Jesus (through his biographers) cast himself as a conservative: “I have come [not] to abolish the Law or the Prophets . . . but to fulfill them” (Matthew 5:17).

So too were America’s revolutionary Founders conservatives by their own lights. They weren’t upheaving the existing order; they were merely obeying “the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God”—what could be more conservative than that? The Founders acknowledged the imprudence of overthrowing a government “for light and transient causes,” yet saw the move as necessary in their case due to the monarch’s pervasive abuses. To adapt Jesus’s words, the Founders came not to abolish English legal traditions, but to fulfill them.

If Jesus and America’s Founders can be conservatives, then anyone can be a conservative. Even Marx can be considered a conservative, in that he casts every movement of history as the culmination of previous movements. Conservatism becomes a tool—a trick, really—to pacify those who romanticize the past.

Every moment in history is partly new, partly rooted in the past. Every moment is at once a revolution and a conservation. To insist that a given incident is one rather than the other usually is not very helpful. Noticing what changes and what stays the [20] same can be more helpful. There is no firm line separating fast change from slow; rather, speed of change lies on a continuum. Ancient Egyptian society stayed largely the same for long periods of time; the Enlightenment and the resulting Industrial Revolution resulted in breathtakingly rapid changes. (Which does the American conservative prefer?) But Egypt was not completely unaffected by the passing of time, and the Enlightenment was not an absolute break with the past. At most, the sensible conservative can say, “This is the wrong type of change,” or, “We should proceed relatively slowly in this given case.”

In many cases, a person calls himself a conservative to avoid saying precisely what he is for, and why. To imply that you are right because your view is the traditional one is to evade the essential questions. Which traditions do you support, which traditions do you oppose, which innovations do you support, which meddlings do you oppose—and why? A conservative without deeper reasons for his positions is a fraud or a huckster; a conservative with reasons is not, fundamentally, a conservative.

Conservatism, Utopianism, and Liberalism

Conservatives erroneously think that they alone stand against utopianism and that liberalism tends toward utopianism. In fact, genuine liberalism rejects utopianism (literally, no place)—despite the fact that some utopians are also confused about this. A political philosophy fancied as liberal by its advocates is not, in fact, liberal, if it aims at some imaginary version of liberty while undercutting the basis of the real thing.

The great economist Friedrich Hayek (who was strongly influenced by Mises) hesitated to call himself a liberal because “American radicals and socialists began calling themselves ‘liberals,’” and “in Europe the predominant type of rationalistic [21] liberalism has long been one of the pacemakers of socialism.”6 Hayek, then, feared that one strain of liberalism tended toward socialist utopianism.

In railing against “rationalistic liberalism,” Hayek points to ideologies that ignore the importance of institutions (particularly those of government), ignore realities of human nature, and seek instead to achieve a “liberty” unmoored from reality. Hayek worries that such utopian ideologies sully the tradition of liberalism; I counter that they are not truly part of that tradition, but opposed to it.

Following Hayek, Jonah Goldberg too rails against utopian “liberalism.”7 Indeed, he suggests that the socialist variants of “liberalism” are what keep him from embracing the mantle of liberalism. He says that “progressives stole the label” liberal. He grants, “The American Founding, warts and all, was the apotheosis of classical liberalism, and conservatism here has always been about preserving it.” Paraphrasing Hayek, he says that only in America could “one . . . be a conservative and a defender of the liberal tradition.” He continues:

I have no problem with people who say that American conservatism is simply classical liberalism. As a shorthand, that’s fine by me. But philosophically, I’m not sure this does the trick. There are many, many, rooms in the mansion of classical liberalism and not all of them are, properly speaking, conservative.

Remarkably, Goldberg, writing for the flagship conservative publication National Review, here is saying that he is a (classical) liberal—a conservative liberal.

[22] But a careful look at Goldberg’s defense of a uniquely conservative sort of liberalism reveals that he doesn’t really have a defense. Rather, he contrasts his conservative liberalism with (illiberal) utopian fantasies such as anarcho-capitalism and with (illiberal) views that are not “grounded in reality,” not attuned to human flourishing, and the like. He fails to capture any ground for a specifically conservative subset of liberalism.

Liberalism properly understood necessarily includes a respect for human nature, an understanding of institutions, and due concern about unintended consequences of social change—things that Goldberg sees as conservative. A “liberalism” without such qualities achieves not liberty but chaos, oppression, and tyranny. Without its careful attention to the institutions of government—particularly the checks and balances needed to hinder political fads, demagogues, and democratic madness—the revolutionary era would not have been the “apotheosis of classical liberalism.”

Genuine liberalism necessarily excludes utopianism; it is inherently conservative in certain respects. So, properly understood, the “conservative” in “conservative liberal” is not a qualifier narrowing the concept; it is an emphasis of certain necessary aspects of liberalism.

But Goldberg and American conservatives generally are not content to find the conservatism inherent in liberalism. Rather, they seek to stitch liberal views with illiberal ones and name this Frankenstein’s monster conservatism.

Consider how often conservatives eagerly sacrifice liberty in the name of religion, tradition, or popular will. People should be free—but not to decide which drugs to consume. Government should protect freedom of expression—and ban certain forms of pornography involving consenting adults. People should be free to trade with others, unimpeded—but not with foreigners. Employers should be free to hire whom they please—except for Mexicans. People should be protected equally under the law—unless they are gay and wish to marry. People should be free to decide how to spend their money—unless the government or some social welfare program really needs it. People generally [23] should be free to live their own lives—except government should force women to carry a just-fertilized zygote to term. (These are all typical but not universal conservative views; for example, Goldberg is “very sympathetic to arguments for gay marriage.”)8

Among less-intellectual politicians and activists, conservatism often becomes an excuse to pragmatically embrace a huge array of statist measures, including expanded government controls of medicine (RomneyCare), corporate bailouts, massive welfare programs, tariffs, subsidies (Marco Rubio as sugar’s sugardaddy), and myriad business regulations. In effect, conservatism becomes a license to cheat on Lady Liberty at will.

Liberalism as Radical and Rational

Liberalism proper is radical, not utopian. It is an alternative to statist, tradition-bound conservatism as well as to socialism and other forms of “progressive” statism.

Radical means “root” or “change from the roots.”9 To be radical means to get to the roots of one’s ideas. Radicalism comes in many stripes. A radical might be a Marxist, a totalitarian Muslim, an ascetic Christian, a pacifist, or a nationalist (as examples). “Radical” refers not to the content of ideas, but rather to taking one’s ideas seriously and seeking to understand those ideas fully and implement them. So a radical liberal—one who takes individual rights seriously and advocates rights-protecting government—should not be confused with a radical who embraces a conflicting ideology, such as socialism. (Ultimately, I would argue that only rational ideas can be truly radical, rooted in sense perception and logic, but that qualification need not further concern us here.)

[24] A liberal is a radical insofar as he seeks to dig down to the deepest theoretical roots supporting individual rights and representative government. For example, Ayn Rand, who used the term capitalism to refer to the socio-economic system of individual rights and free markets (i.e., liberalism), said of those who advocate her beliefs, “[We] are not ‘conservatives.’ We are radicals for capitalism; we are fighting for that philosophical base which capitalism did not have and without which it was doomed to perish.”10

A radical liberal tends to look fundamentally to reason, not faith or tradition, for guidance; in this sense, liberalism is the opposite of conservatism. Although the modern conception of individual rights has roots deep in history, in the main it is a product of the reason-centered Enlightenment. Liberalism’s reliance on reason is precisely why conservatives distrust it—but they are wrong to do so.

Conservatives worry that, because liberalism is rooted in reason, it inherently tends toward “scientific” socialism. Just look at the mass-murdering, atheistic socialist regimes of the Twentieth Century, conservatives urge. Here we needn’t get deeply into the matter that Marx, the Young Hegelian who modified his predecessor’s delusional metaphysical rantings, was not actually an advocate of reason. As C. Bradley Thompson summarizes, far from embracing evidence-based reason, “Marxism represents a revolt against the laws of reality.”11 For our purposes, the key point is that liberalism rejects rationalist socialism and shares essentially nothing in common with it. (“Rationalism” here refers, not to [25] evidence-based reason, but to superficially logical arguments detached from reality.)12

Liberalism rejects the collectivist notion that allegedly “rational planners” can, for the “good of society,” coercively run people’s lives or the economy as a whole. Such “planners” in reality are pervasively ignorant about people’s values and about how people accomplish their goals, and they typically lack the incentives to plan well even if they could do so. As Mises eloquently explains, such centralized, allegedly rational planning actually impedes or destroys people’s ability to rationally plan their own lives. True, a liberal order leaves individuals free to run their lives rationally or not. But if individuals choose to live by reason, government does not stop them; and if they do not, government does not force others to engage with them.

Genuine liberalism is radical, not rash; rational, not unmoored from reality. Conservatives and others are wrong to conflate liberalism with socialism. Radical liberals understand and feed the roots of liberty; rationalist socialists uproot the plant.

I think for our purposes here I’ve adequately outlined the relationship between liberalism and conservatism. Next, it will be helpful to see how liberalism fits with other common political terms, starting with left and right.

The Problem with Left and Right

Americans tend to use “left” as a synonym for Progressive or socialist tendencies and “right” for conservative and free market ones.

In addition to the fact that conservatives often oppose free markets, an obvious problem immediately asserts itself: “Right” often also refers to (socialistic) fascists and to (collectivist) racists. [26] But the “right-wing” views of genuine liberals are antithetical to the views of “right-wing” fascists and racists.13

A term that packages together such disparate and contradictory things sows more confusion than clarity. Undoubtedly Marxists (and their fellow travelers) will claim that liberal capitalism tends toward fascism and racial nationalism, but that’s nonsense. Liberalism embraces local and international free trade, calls for rights-respecting government, and demands equality under the law. Packaging it with racism and nationalist socialism is dishonest and absurd. Hence, it makes no sense to distinguish “center right” from “far right” as the terms currently are used; there can be no continuum of fundamentally unlike things.

I do think that ideological movements of the left (as understood today) have something in common—statism, meaning (roughly) advocacy of government controls and wealth transfers. So there is a continuum of socialist-left politics, and “center left” is less statist than “far left.” For example, the “left-wing” Scandinavian welfare states do have something in common with the murderous and oppressive “left-wing” Soviet regime—the forced transfer of wealth—but the differences are far more pronounced. So, unlike the term right-wing as it is usually used, the term left-wing at least has a coherent meaning.

Replacing the term leftist with statist would be much more descriptive of what we’re actually talking about. When I use the term statist, I do mean it pejoratively, but that’s because I think that statism is wrong. In the same way, I’ve used leftist pejoratively. Today’s leftists should have no more problem embracing the statist label—Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton loudly brag about using the state to “invest in the economy” and the like—than I have embracing the capitalist label, in its origins a pejorative term for a free economy. [27] So the statists are on one side, in my scheme; the liberals are on the other. If statists don’t like that term, I suggest that’s because they wish to obscure the nature of their political beliefs.

A qualifier: I use statism to refer to advocacy of government action above and beyond the protection of individual rights. To anarchists, I too am a statist because I advocate a rights-respecting government, not the abolition of government. But there is an important difference between a government that acts only to protect individual rights and a government that acts to transfer wealth and control peaceable people. Theorists such as Mises and Rand have long used the term statism as I do here.

There is another problem with the way that most people use left and right today: It does not mesh well with the historical uses of those terms. Originally, the terms referred to the seating of French politicians in 1789: Those on the right favored the established order; those on the left, revolution. Originally a “leftist” was closer to a liberal (as I use the term) than to a socialist.14

Yet a liberal shares some of the concerns of those on the traditional right. Max Forrester Eastman suggests that, originally, a leftist “stood for the individual and his liberties” while a rightist backed the “constituted authorities.”15 Well, if the constituted authority is a tyrannical monarchy, then a liberal is against it. But a liberal is not against authority per se, as when police lawfully arrest someone suspected of murder. The liberal embraces both liberty and lawful authority. Indeed, the rights of the individual can be protected only by a rights-respecting government with due authority to fulfill its mandate; properly, individual rights and government authority go hand in hand. So, in this sense, a liberal [28] represents the union of left and right, of individual liberty and a government authorized to protect it, rather than a choice of one or a rejection of both. Liberalism flies with both these wings and cannot fly without them.

Can the terms right and left be salvaged by redefining them? Craig Biddle of the Objective Standard (for which I used to write) plausibly argues that we should use “right” to refer to what I’m calling liberal and “left” to refer to statist. But his case seems contrived; he says that “the right” corresponds with the term rights (as in individual rights) and that the protection of rights is “morally right.”16 Biddle makes the terms coherent, but I think the term right-wing has become too muddied for him to salvage it. Biddle now uses the term “liberal right,”17 which is fine, although ultimately I think it is better to drop out the term “right” and fully reclaim the term liberal.

For now, given how widespread the use of the terms left and right are, I propose to continue using the terms where useful, but only with qualifiers or context that clarifies the intended meaning (such as Biddle’s “liberal right”). The term “statist left” clearly refers to advocacy of government force (beyond the protection of rights). “Civil liberties left” refers to the genuinely liberal tradition of upholding freedom of speech and the like. The newly popular terms “illiberal left,” “regressive left,” and “authoritarian left” aptly describe the movement that seeks to squash political [29] debate (especially on college campuses) and to excuse horrific acts of select groups (especially totalitarian jihadists).18

What is critically important is that we stop using the terms right and left to package together contradictory ideas, such as economic liberty and racism (“right”) or freedom of speech and an intrusive state (“left”). The true liberal is neither left nor right, if those terms refer to collectivist socialism and racial fascism, or both left and right, if they refer to individual liberties and properly constituted government.

The Long-Term Reclamation of Liberalism

Obviously, genuine liberals cannot just go around in modern America, proclaim themselves liberals without any context, and expect people to understand what they’re talking about. For too many decades people have abused the term.

Liberals should declare themselves to be such in order to reclaim the name of their political beliefs and to help clarify people’s language and thinking. But liberals need to proclaim their liberalism with relevant qualifiers and context, until such time as the term is broadly understood to mean what its etymology and history imply.

Consider some examples of sensible liberal answers to inquiries about political views:

“I’m a liberal in the classical sense, meaning I advocate individual rights, free markets, and constitutional government.”

“If ‘left’ refers to individual freedom and ‘right’ refers to tradition and law and order, then in a way I’m both. I advocate America’s tradition of constitutional government for the protection of individual rights. But if left means socialism and right means fascism or racial nationalism, then I reject both.”

[30] “People who usually call themselves liberals today are nothing of the sort. They are statists, not liberals. They advocate rights-violating government that confiscates people’s wealth and controls their lives. That’s not liberal and progressive; it’s illiberal and regressive. I’m a genuine liberal; I advocate individual liberty.”

“Liberalism properly understood is neither about the isolated individual nor about a society that crushes individual rights and values. Rather, it refers to a system in which individuals freely pursue their values in voluntary association with others, in accordance with others’ equal rights.”

I have now made the essential case for reclaiming liberalism, and I have described the basics of how to accomplish the reclamation. Yet there is one more matter I need to address: Why not embrace the newer term libertarian? After all, my policy views overlap substantially with those of self-described libertarians. Wouldn’t it be easier just to buy into the libertarian label than to reclaim the term liberal? No; libertarianism is not liberalism, and it is a mistake for liberals to call themselves libertarians.

Why Not Libertarianism?

“Libertarian” is by now a widely recognized term that means, loosely, “socially liberal and fiscally conservative.” The 2016 Libertarian presidential candidate Gary Johnson helped popularize this sort of description.19 But such language embeds the sorts of confusions discussed above. Does “socially liberal” imply that government should punish businesses that discriminate against homosexuals, as Johnson endorses?20 Does “fiscally conservative” mean support for tariffs, corporate [31] subsidies, and a welfare state, as it does for many self-described conservatives? If we take “fiscally conservative” to mean free-market in some sense, then economic liberty is presumed by Johnson’s language to be outside of liberalism rather than a part of it. In such ways libertarianism confuses the discussion rather than clarifies it.

As some people describe it, libertarianism just is liberalism. For example, David Boaz of the flagship libertarian think tank the Cato Institute lists a package of “libertarian” beliefs including individualism, individual rights, the rule of law, and free markets.21 Apparently part of the idea is that the term liberal has been so corrupted that it’s easier to use the newer term libertarian instead. But it is a tactical mistake to continue to cede the term liberal to anti-liberals, as doing so keeps alive the usual confusions.

There is a much deeper problem: Libertarianism does not just mean liberalism; it means most prominently an antagonism toward government as such. Perhaps this remark will seem surprising to self-described libertarians who admit the need for (some) government. My claim is not that all libertarians are anarchists; rather it is that libertarianism tends to foster animosity toward government, and, ultimately, it tends toward anarchy.

As an indication of the problem, consider that Jeffrey Tucker, an outspoken anarchist (and in many respects otherwise a wonderful writer), is (as of late 2016) the Director of Content for the Foundation for Economic Education, an important free-market institution since 1946. Tucker, too, wishes to reclaim the term liberal—for anarchists. He says that “genuine liberalism has continued to learn and grow and now finds a more consistent embodiment in what is often but awkwardly called libertarianism [32] or market anarchism, both of which are rightly considered an extension of the old liberal intellectual project.”22

The Institute for Humane Studies, an organization that sponsors numerous libertarian events (some of which I’ve attended and enjoyed), likewise wants to extend liberalism to anarchism:

The libertarian or “classical liberal” perspective is that peace, prosperity, and social harmony are fostered by “as much liberty as possible” and “as little government as necessary.” . . . Libertarian is not a single viewpoint, but includes a wide variety of perspectives. Libertarians can range from market anarchists to advocates of a limited welfare state, but they are all united by a belief in personal liberty, economic freedom, and a skepticism of government power.23

Here we get the idea of what it typically means to be a libertarian: It is either to embrace anarchy outright or else to grudgingly think that some given level of government is practically “necessary,” despite the theoretical ideal of no government. Some libertarians think government can feasibly be reduced only to a modest welfare state; others think it can be abolished. The sentiment remains that government is inherently bad, to be tolerated only if it must be. Libertarians tend to equate freedom with the absence of government, and libertarians are more “pure” the more government they’re willing to cut. The main concern for libertarianism is how much government there is.

[33] But the absence of government does not mean the presence of liberty. On the contrary, a rights-respecting government is necessary for liberty. Mises rightly rejects the notion that the best government is that “which governs least.” Instead, he points out, “Government ought to do all the things for which it is needed and for which it was established. Government ought to protect the individuals within the country against the violent and fraudulent attacks of gangsters, and it should defend the country against foreign enemies.”24 So the proper measure of good government is not its size, however that is calculated; rather, it is that it serves its proper purpose of protecting rights. If a government faces large-scale foreign aggression or widespread internal violence, as examples, it properly expands in size such that it can address the problems at hand.

To the genuine liberal, smaller government is not necessarily better. A government that inadequately addresses crime or that inadequately adjudicates property disputes (for example) is too small, and it should seek greater resources to accomplish such tasks.25

Although anarchism is in my view a fundamentally anti-liberal position, I am not arguing that libertarians, including explicitly anarchist ones, should not be included in the liberal tradition. Many of today’s top libertarian scholars, including economist Bryan Caplan and philosopher Michael Huemer, are anarchists, but they are not only anarchists. They often do pathbreaking work in a variety of fields supportive of the broadly liberal project. They are liberals despite their anarchism, not because of it.

[34] Of course, the so-called anarcho-capitalists (and I used to count myself as both an anarchist and a libertarian) will continue to argue that anarchism ultimately is the truest form of liberalism. I’m not going to further pursue that debate here; I will contend only that the distinction is important enough that liberals who think properly constituted government is necessary for the protection of rights ought not count themselves as libertarians.

History also poses a challenge for those who would use libertarianism to mean liberalism. In its roots the term was much more closely associated with socialist movements than with free-market ones. As Noam Chomsky observes, “The term libertarian as used in the US means something quite different from what it meant historically and still means in the rest of the world. Historically, the libertarian movement has been the anti-statist wing of the socialist movement. Socialist anarchism was libertarian socialism.”26

Given the myriad problems with the term libertarian, and the obvious advantages of the term liberal to describe an order based on individual rights, liberalism clearly wins the day.

Renewing the Fight for Liberty

Today’s debate between “liberals” (as usually understood) and conservatives is profoundly confused. Very often, that “debate” revolves around which form of statism to more fully embrace. The detestable 2016 presidential election with its two major-party statists is merely an indicator of the broader trend.

Liberalism (real liberalism) is a movement worth saving. Liberals recognize the moral right of individual to pursue their own lives and values, free from the coercion of others. Liberals recognize the need for properly constituted government to protect people’s rights equally. Liberals embrace the economic [35] progress made possible by free-market capitalism. Liberals call for human relationships based on mutual consent, not force. Liberals recognize the magnificent achievement of the United States government—and seek to more fully realize its promise of liberty.

It is time for those of us who advocate liberty to get our voice back, to get our name back, to once again proudly proclaim that we are liberals.

[36]

The Irrationality of Neil deGrasse Tyson’s Rationalia

If only society could be governed by a rational elite, what a wonderful world it would be. Or at least various theorists have speculated since Plato penned the Republic.

Astrophysicist and science popularizer Neil deGrasse Tyson is the latest in a long line of utopian theorists. He set off a spirited debate when, on June 29, he Tweeted: “Earth needs a virtual country: #Rationalia, with a one-line Constitution: All policy shall be based on the weight of evidence.”27

Apparently at least some people found the idea appealing; over ten thousand people retweeted the remark, and over twenty-four thousand “liked” it. Of course, Tyson’s remark also drew pointed criticism. Robert F. Graboyes, Jeffrey Guhin, S. Shane [37] Morris, Kevin D. Williamson, Kelsey D. Atherton, Jesse Singal, and David Roberts are among those who criticized Tyson.28

The main thrust of the criticisms of Tyson, with which I heartily agree, is that self-proclaimed “rational” people very often, in fact, are not rational. Just consider how widespread eugenics was among the scientific elite not too many decades ago.

Another problem is that the natural sciences that Tyson invokes do not, by themselves, generally imply particular political conclusions, and thinking they do is hubris. For example, biology can tell us many interesting things about the fetus at various stages of development; it cannot, however, tell us whether or how to restrict abortion. And, as Roberts points out, the scientific facts about climate change do not, by themselves, tell us what we should do about it. (Alex Epstein plausibly argues we should respond to climate change by using more fossil fuels.)29

[38] Then there is the critical problem of who gets to decide who is sufficiently rational to be in charge. Who watches the watchers, who guards the guardians? People tried to create real-world Rationalias in the Twentieth Century, several times. Communism was supposed to be about rationally and scientifically planning the economy. Not only did this lead to allegedly rational planners governing by profound ignorance, causing widespread devastation; it led to despicable people taking charge. The Communists committed the worst mass murders in history in terms of number of victims, followed by the (allegedly also rational) National-Socialist German Workers’ Party.30 Socialist versions of Rationalia failed repeatedly and spectacularly.

Arch-skeptic Michael Shermer suggests the obvious cure for the problem of guarding the guardians: Set up government institutions that foster rational outcomes. Shermer is much more sensitive to the importance of government institutions than Tyson seems to be. He claims that “Rationalia already exists”; it is “the Enlightenment experiment running here since 1776.”31 It is the experiment of representative democracy, he adds, which further allows policy experimentation.32

Certainly the Founders strove to be rational in setting up the United States government, looking to the guide of history and to the requirements of human nature. For example, as Federalist 51 points out, “A dependence on the people is, no doubt, the primary control on the government; but experience has taught [39] mankind the necessity of auxiliary precautions”—mainly involving constitutional government with checks and balances.33

Of course, the “Rationalia” of representative and constitutionally limited government hardly guarantees that rational people will run government—our experiences with the 2016 presidential election should prove that beyond any doubt. Yet Shermer can sensibly claim (and I agree) that the general sort of government we have is the best we can rationally hope for (it allows for internal improvements, which we need), and that it gives us the best hope for rational outcomes. As the saying goes, constitutional democracy is terrible, but it is less terrible than other forms of governance.

We should keep in mind that Tyson is talking about a “virtual” country, not a real one. Yet he clearly means his virtual world to be in some respects a model for the real world. It is unclear (to me) whether and to what degree Tyson buys into the rational requirement of representative, constitutionally limited government. Without a means of real-world implementation, Tyson’s version of Rationalia remains purely utopian.

If Tyson is saying that a “rational” elite should run society—and his remarks can easily be interpreted that way—then he’s obviously and dangerously wrong.

Yet in a deeper sense I take Tyson’s side. Some of Tyson’s critics essentially argue that people cannot be fully rational, therefore Rationalia (in the real world) won’t work. I agree with Tyson that we can be rational, and we can, in fact, build a society on rational principles.

Tyson’s problem is that he doesn’t know which principles are rational in the realm of politics. His main error is smuggling in false philosophic premises as his standard for what counts as “rational” policy. Thus, my central criticism of Tyson is not that Rationalia is impossible—I think it is possible, in the sense [40] outlined by Shermer—it is that Tyson’s particular version of Rationalia is fundamentally irrational.

Tyson offers a much more detailed account of his Rationalia in an August 7 Facebook post.34 Here we can see Tyson’s underlying fallacies at work.

I want to walk through Tyson’s key remarks and make some first-round criticisms, then step back and draw some broader conclusions.

Tyson says he uses the term “policy” broadly:

Examples of Policy would be a government’s choice to invest in R&D, and if so, by how much. Or whether a government should help the poor, and if so, in what ways. Or how much a municipality should support equal access to education. Or whether or not tariffs should be levied on goods and services from one country or another. Or what tax rate should be established, and on what kinds of income.

Clearly Tyson envisions a powerful government. He does not question whether government should impose taxation—that it should is a given in Tyson’s world—he allows room only for debating the nature of taxation. Government “investing” in scientific research is automatically neither in nor out on moral grounds; it depends on the “evidence” about it.

Tyson continues, “In Rationalia, since weight of evidence is built into the Constitution, everyone would be trained from an early age how to obtain and analyze evidence, and how to draw conclusions from it.”

Trained . . . by whom? Obviously Tyson has the government in mind. And if a parent does not wish his child to be “trained” by Tyson’s educators “from an early age,” what then? If Tyson really means [41] “everyone,” then he means government should send agents with guns to forcibly remove children from noncompliant parents. I suspect Tyson would walk back some of his remarks if pressed; he doesn’t seem to have thought through some of them very carefully.

Next: “In Rationalia, you would have complete freedom to be irrational. You just don’t have the freedom to base policy on your ideas if the weight of evidence does not support it.”

Obviously Tyson does not really mean “complete freedom”; for example, people wouldn’t be free to murder others or (presumably) to engage in female genital mutilation. But what else would Tyson forbid? He’s not clear. Would religious parents have “complete freedom” to educate their children as they see fit?

A bit later in his piece, Tyson renegotiates his promise of “complete freedom” for the individual. Instead, he writes, “In Rationalia, research in psychology and neuroscience would establish what level risks we are all willing to take, and how much freedom we might need to forfeit, in exchange for comfort, health, wealth and security.” Hello, 1984.

Note here that Tyson seems to presume that an individual is automatically irrational if he demands freedoms that clash with the risk-aversion, “comfort, health, wealth [or] security” of others. Does Tyson mean a majority? Does he think some utilitarian collective happiness calculation is possible and desirable? He is entirely unclear. Obviously we are not “all” going to agree about appropriate levels of risk, “comfort,” and the like—so what is the standard by which the freedom of dissenters will be squashed?

Then there’s this: “In Rationalia, you could create an Office of Morality, where moral codes are proposed and debated”—and, presumably, imposed by force. Sort of like what the “rational” Communists did. (The practitioners of totalitarian Islam also have their Offices of Morality, which they’d claim are perfectly rational.)

I’m sure that Tyson does not intend a totalitarian outcome. I am equally sure that a future “scientific” totalitarian could [42] plausibly claim to be in complete compliance with the terms for Rationalia that Tyson lays out.

That Tyson is deeply statist in political orientation is beyond reasonable doubt: He wants a powerful government to substantially control key aspects of each person’s life, including each person’s wealth, education, and morals. What is the source of this statism?

Undergirding Tyson’s statist vision of Rationalia is a philosophic presumption of collectivism, the view that society as a whole is the basic standard of value, and that individuals, their values, and their proclaimed rights may be sacrificed for the sake of society.

Does an individual not wish to subject his children to the government’s “training” regimen? Not wish to finance government-approved R&D or “art in schools” or government research into “the sciences that study human behavior” or whatever else the “rational” class might concoct? Not wish to surrender his freedoms for the proclaimed “comfort, health, wealth and [or] security” of others? Not wish to obey the dictates of the Office of Morality? Too bad. The individual, his values, his rights (not that Tyson seems to recognize the existence of rights), his liberties, his wealth, his children, presumably his very life, all may be demanded by the self-proclaimed “rational” rulers.

What is the rational basis of Tyson’s collectivism? He offers none. His entire “rational” structure is built on an irrational, unjustified (and unjustifiable) philosophic presumption.

Of course, in the scope of a short article such as this, I cannot justify the moral theory that an individual rightly pursues his own life and values, nor the political theory that individuals have rights. The point here is that, to establish that your politics are rational, you have to actually recognize the moral underpinnings of your politics and, ultimately, show that they, too, are rational. Tyson doesn’t even seem to realize that he’s presuming unjustified collectivist moral premises.

Some might deem my criticisms of Tyson overly harsh. Isn’t Tyson in important ways just arguing for the status quo? Obviously [43] government today confiscates people’s wealth, runs schools, finances R&D, prohibits various “immoral” behaviors, and so on—in important ways Tyson follows convention, not reason. Yes, I decry the collectivism at work in today’s politics. But at least the (often implicit) collectivism of today is mixed with an (often explicit) individualism, and at least it does not formally bear the mantle of rationality. By claiming to base a society on rationality, and by grounding that society on collectivist premises, Tyson gives collectivism a dangerously broader sanction and potential. Quite simply, collectivism taken to its “rational” conclusions results in totalitarianism, always and necessarily.

I’ll pick up the fundamental moral debate another day. Here I will conclude by pointing out that Shermer’s version of Rationalia—the Founders’ version—is compatible with individualism: The view that each person morally pursues his own values and happiness, consonant with the rights of others. (I don’t agree with all of Shermer’s particular political conclusions.) The project of American governance is, at its core, based on people’s “unalienable Rights,” chiefly each person’s rights to “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

Tyson includes this gem in his discussion: “In Rationalia, . . . [e]veryone would have a heightened capacity to spot bullshit wherever and whenever it arose.” Thankfully, we don’t need to live in Tyson’s Orwellian version of Rationalia to spot his bullshit collectivist moral premises.

[44]

Sam Harris’s Collectivist Politics

Sam Harris—neuroscientist and famed atheist—holds that matters of right and wrong, good and bad are discoverable, objective facts, properly the subject of a science of ethics. In his 2010 book The Moral Landscape, he writes in his introduction, “questions about values—about meaning, morality, and life’s larger purpose—are really questions about the well-being of conscious creatures. Values, therefore, translate into facts that can be scientifically understood” (p. 1).35

So far, so good. Unfortunately, Harris quickly veers off the scientific track by defining “well-being” in terms of the moral theory of utilitarianism. Utilitarianism holds that the standard of moral value is “the greatest good for the greatest number”; in practice, this means the individual must self-sacrificially serve the interests of society.

Harris explicitly ties his views to the utilitarian tradition of Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill, though he says “[c]onsequentialism has undergone many refinements” since the days of Bentham and Mill (p. 207, n. 12). In this tradition, the standard of moral value is the aggregate happiness of all people. [45] Although Harris recognizes some of the problems with attempting to aggregate the well-being of everyone, he insists that “human welfare must aggregate in some way” (pp. 68, 72).36 Indeed, the “some way” in which utilitarianism aggregates human welfare is by sacrificing the individual to the alleged greater good of the group. If that sounds ominously similar to the moral foundation of the political nightmares of the 20th century, that’s because it is.

Remarkably, Harris is, at times, quite open about the implications of utilitarianism and serious about promoting them, noting that the doctrine can justify the murder of individuals—or large numbers of individuals—for the presumed greater good. For example, Harris writes:

Admittedly, it is difficult to know how we should treat all of the variables that influence our judgment about ethical norms. If I were asked, for instance, whether I would sanction murder of an innocent person if it would guarantee a cure for cancer, I would find it very difficult to say “yes,” despite the obvious consequentialist argument in favor of such an action. If I were asked to impose a one in a billion risk of death on everyone for this purpose, however, I would not hesitate. (p. 143)

Harris goes further, wondering whether “it would be ethical for our species to be sacrificed for the unimaginably vast happiness of some superbeings.” He answers: “Provided that we take the time to really imagine the details (which is not easy), I think the answer is clearly ‘yes.’” Although Harris notes that “there is no compelling reason to believe that such superbeings exist,” he acknowledges that, on his theory, if they did, humans would be morally bound to willingly accept their own annihilation (p. 211, n. 50).

[46] At other times, Harris walks back from the logical implications of his theory, opting instead for a watered-down utilitarianism in which individuals succumb to their “selfish” nature and act only to a limited extent for the happiness of all “conscious creatures.” In other words, in light of complications that arise from his theory, he recommends cheating on it. And, as an example of appropriate ways to cheat, Harris takes a page from his own life.

Citing such tragedies as the fact that some “people on earth needlessly starve to death,” Harris writes of his own frequent inattention to such matters: “I am less good than I could be. Which is to say, I am not living in a way that truly maximizes the well-being of others” (p. 82). How does Harris rationalize acting against his own standard of value? How, for instance, does he justify failing to reduce his own (and his family’s) standard of living to near-subsistence so that he can send the residual to the starving people of the world? Essentially, he argues that people (himself included) are too narrowly “selfish” to fully live up to the utilitarian ideal; people are not constituted such that they can act fully morally. As he puts it, “We are not, by nature, impartial—and much of our moral reasoning must be applied to situations in which there is tension between our concern for ourselves, or for those closest to us, and our sense that it would be better to be more committed to helping others” (p. 40). The best we can do, says Harris, is to resolve the conundrum pragmatically: “What we can do is try, within practical limits, to follow a path that seems likely to maximize both our own well-being and the well-being of others. This is what it means to live wisely and ethically” (p. 85).

Harris attempts to persuade readers that acting more in accordance with the utilitarian ideal would make them personally happier, but he cannot persuade even himself of this:

I know that helping people who are starving is far more important than most of what I do. I also have no doubt that doing what is most important would give me more pleasure and emotional satisfaction. . . . But this knowledge does not change me. I still want to do what [47] I do for pleasure more than I want to help the starving. . . . I would be happier if I were less selfish. This means I would be more wisely and effectively selfish if I were less selfish. (p. 83)

Harris recognizes that upholding his utilitarian standard of value—the greatest happiness for the greatest number—is simply impossible. Hence, he condones cheating on it.

To the degree that Harris is true to his collectivist underpinnings, they push him toward totalitarian politics.

Harris acknowledges that “many people are simply wrong about morality” (p. 87). Within an individualist theory of morality, that poses no special problem: So long as people don’t aggress against others, they are free to be wrong; and if some people do aggress against others, they are properly prosecuted as criminals. Within Harris’s utilitarian framework, however, the fact that many err in their moral thinking and acting creates a moral crisis for everyone. And, as Harris has admitted, no one—including Harris—can uphold the utilitarian ideal of serving the greatest happiness of the greatest number.

If people morally should serve the greater good of the group but do not, can they be left free to be immoral? How will we know whether people’s actions are really in the best interest of the group? Who will decide such matters? According to Harris, “moral experts” will decide.

That others have noticed totalitarian implications in Harris’s theory prompted him to repeatedly deny such implications. For instance, when Harris wrote that “only genuine moral experts would have a deep understanding of the causes and conditions of human and animal well-being” (p. 36), he added the following in a footnote:

Many people find the idea of “moral experts” abhorrent. Indeed, this ramification of my argument has been called “positively Orwellian” and a “recipe for fascism.” . . . [T]hese concerns seem to arise from an uncanny reluctance to think about what the concept of “well-being” actually [48] entails or how science might shed light on its causes and conditions. The analogy with health seems important to keep in view: Is there anything “Orwellian” about the scientific consensus on the link between smoking and lung cancer? (p. 202, n. 17)37

But this analogy fails. On an individualist conception of morality, nothing in a scientific finding on the physiological effects of smoking implies that the government should ban or restrict smoking (at least not for adults on private property). When people are seen as individuals—with each individual being morally responsible for his own life, health, and happiness—people are free to act as they choose so long as they do not violate the rights of others. If someone chooses to ignore scientific findings or medical experts and proceeds to smoke himself ill, that is his choice and his problem.

On a collectivist moral ideal, however, individuals are not seen as responsible for their own lives, health, and happiness; rather, they are regarded as responsible for everyone’s life, health, and happiness. To be moral, according to utilitarianism, people must act so as to achieve the greatest happiness for the greatest number—and they must sacrifice their personal goals and values to achieve that end. This collectivist moral framework necessitates a collectivist political program. If the collective or the “moral experts” decide it is best for the individual to be forbidden from smoking—or forbidden from doing anything else, or required to do anything else—then the individual morally must obey.

Concerns about Harris’s call for “moral experts” to determine the best ways for people to live up to the utilitarian ideal are hardly quelled by his additional call for manipulating individuals’ brains. Consider Harris’s following remarks (in which he leaves “we” undefined):

[49] If . . . we can one day manipulate the brain so as to render specific behaviors and states of mind more pleasurable than they are now, it seems relevant to wonder whether such refinements would be “good.” It might be good to make compassion more rewarding than sexual lust, but would it be good to make hatred the most pleasurable emotion of all? (p. 196, n. 20; see also pp. 102, 109)

After denying “that the mere existence of the Nazi doctors counts against my thesis,” Harris writes:

If we were ever to arrive at a complete understanding of the human mind, we would understand human preferences of all kinds. Indeed, we might even be able to change them. . . . Consider how we would view a situation in which all of us miraculously began to behave so as to maximize our collective well-being. Imagine that on the basis of remarkable breakthroughs in technology, economics, and politic skill, we create a genuine utopia on earth.38

Harris writes this as though nothing were troublesome about the notion of “moral experts” and some undefined “we” “manipulating” people’s brains to “create a genuine utopia on earth” through “breakthroughs in technology, economics, and politic skill.” A skeptic, however, perhaps someone with an “uncanny reluctance” to think about things from Harris’s perverse perspective, might respond that the 20th century produced quite enough such “breakthroughs” on the road to utopia. And the utilitarian regimes of that century did not yet have the power of today’s or tomorrow’s neuroscientists to manipulate people’s brains.

[50] But just imagine, Harris continues, if we could alter the brains of everyone by “painlessly deliver[ing] a firmware update to everyone”:

Now the entirety of the species is fit to live in a global civilization that is as safe, and as fun, and as interesting, and as filled with love as it can be. . . . [I]f you care about something that is not compatible with a peak of human flourishing—given the requisite changes in your brain, you would recognize that you were wrong to care about this thing in the first place. Wrong in what sense? Wrong in the sense that you didn’t know what you were missing.39

How is Harris’s proposal here different from the Borg Collective in Star Trek? What if an individual does not care to undergo brain surgery to discover what he has been missing? Would the “moral experts” say, as do the Borg, “Resistance is futile?”

Because Harris’s moral framework evaluates individuals and their actions by the standard of collective well-being, it is incompatible with the principle of individual rights. Harris appears to acknowledge and accept this: “Some people worry that a commitment to maximizing a society’s welfare could lead us to sacrifice the rights and liberties of the few wherever these losses would be offset by the greater gains of the many.” Not to worry, he says: “To the degree that treating people as ends in themselves is a good way to safeguard human well-being, it is precisely what we should do” (p. 79).

Of course, “treating people as ends in themselves” only insofar as that serves the collective “good” is not treating people as ends in themselves; it is treating them as means to the ends of the collective. And “to the degree that treating people as ends in themselves” does not serve the collective good—a determination [51] to be made by the “moral experts”—individuals and their rights must be sacrificed.

So what is the individualist alternative?

Harris is right that morality should be based in reality and viewed as a science discoverable through reason. He is right that morality pertains to well-being, and that ethics prescribes the means to achieving it. But he is wrong in embracing a utilitarian, collectivist standard; wrong in sanctioning the sacrifice of individuals to the collective; wrong in obliterating the principle of individual rights and paving the way for more totalitarianism.

Decades before the publication of Harris’s book, Ayn Rand formulated an individualist morality that anticipates everything salvageable in Harris’s work and avoids all of its problems.

Unfortunately, at least as of May 2012, Harris refuses to read Rand’s works, saying “my copies of [Rand’s novels] The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged simply would not open.”40 (Isn’t there a “firmware update” for that?) Not surprisingly, in attempting to describe Rand’s ethical views he fundamentally misrepresents them.41

If Harris would consider the possibility that collectivism is false, he would be closer to finally being able to articulate a viable alternative to the moral relativism and religious dogma he so rightly despises.

[52]

“You Didn’t Build That”—Obama’s Ode to Envy

Barack Obama’s July 13, 2012 speech,42 in which he tells business owners, “you didn’t build that,” has rightly generated enormous criticism. But why did he say it? Before we turn to that question, let’s review exactly what Obama said:

[I]f you’ve been successful, you didn’t get there on your own. . . . I’m always struck by people who think, well, it must be because I was just so smart. There are a lot of smart people out there. It must be because I worked harder than everybody else. Let me tell you something—there are a whole bunch of hardworking people out there.

If you were successful, somebody along the line gave you some help. There was a great teacher somewhere in your life. Somebody helped to create this unbelievable American system that we have that allowed you to thrive. Somebody invested in roads and bridges. If you’ve got a business—you didn’t build that. Somebody else made [53] that happen. The Internet didn’t get invented on its own. Government research created the Internet so that all the companies could make money off the Internet.

The point is, is that when we succeed, we succeed because of our individual initiative, but also because we do things together.

This speech is remarkable only for its ludicrousness. (It is certainly not remarkable for its originality; as others have noted, Obama took a page out of Elizabeth Warren’s campaign book.43 Then again, Obama would say she didn’t write that.)

Obama wishes us to believe that the successful—whatever their field and scale of success—are wrong to attribute their success to applying their minds and working hard. Unfortunately for Obama, rational Americans know that his claim contradicts the facts surrounding the achievements of every productive industrialist, producer, and creator, who succeeds by thinking, planning, and working hard.

Examples range from J. D. Rockefeller, who revolutionized the oil industry; to the Wright brothers, who pioneered heavier-than-air human flight; to Thomas Edison, who developed a usable electric light bulb (among other innovations); to Ayn Rand, who wrote great novels on the themes of independence, individual productiveness, and the role of reason in man’s life; to Steve Jobs, who revolutionized the computer, music, and film industries.

Obama wishes us to believe that, because not every “smart,” hard-working person reaches the pinnacle of success, that somehow diminishes the achievements of those who do. True enough, some “smart” people misapply their intelligence, [54] for instance, by becoming animal “rights” activists or Marxist community organizers. Others go into business without having the right business plan, the right motivation, the right leadership skills, or the right good or service for their intended market; indeed, only a third of businesses survive their first decade.44 Often entrepreneurs fail numerous times before developing a successful business. Rational Americans understand that, while not every smart, hard-working person builds a successful business, that does not alter the fact that those who do build successful businesses do so by thinking, planning, and working hard.

Obama also wishes us to believe that, because successful producers learned something from government teachers, used government roads and bridges, employed government research, and the like, this means they don’t really own their success or wealth. Rational Americans know full well that the government funds such things by forcibly confiscating the wealth of producers. Rational Americans also know that a bum is as free to use a government bridge as is a successful business owner, but the business owner chose to apply his intelligence and work hard to build something great.

Finally, to mask the inanity of what he just said, Obama mentions that “individual initiative” perhaps has something to do with a producer’s success. But, in addition to seeing through Obama’s flagrant contradictions, rational Americans see this subordination for exactly what it is: an attempt to insignificantly mitigate what he said before, while leaving what he said before as his main and emphatic message.

Of course, that Obama flouts logic and observable facts is obvious to anyone who spends even a few moments evaluating his claims. Why, then, does he spout such nonsense?

[55] To understand the atmosphere in which Obama delivered his remarks, watch the video.45 When Obama tells business leaders, “You didn’t get there on your own,” some in the crowd chant, “That’s right!” When Obama ridicules business leaders for thinking they’re “just so smart,” many in the crowd meet his comments with jeering laughter.

The purpose of Obama’s speech was not to present serious arguments about the causes of success in business. His claims are ridiculous on their face. Obama’s purpose was to give envious Americans the pretext they need to openly loathe those who have been successful—and to vote accordingly.

If the successful didn’t really earn their success—and thus the wealth that comes with it—then there’s nothing wrong with “spreading their wealth around” to those who have not been so successful. If no one is responsible for his success, then no one has a right to the fruits of his success, and thus those who haven’t been successful have the same right to those fruits. And if the successful resist the “noble” effort to redistribute what is “really” the community’s wealth, then they are evil—or so Obama wishes us to believe.

In reality, anyone who develops a new technology, writes a great novel, brings an innovative new product to market, or in any other way earns success, thereby deserves the fruits of that success. Unfortunately for Obama, rational Americans know this, and rational Americans will win this debate.

[56]

The Justice of Income Inequality Under Capitalism