Ari Armstrong's Web Log (Main) | Archives | Terms of Use

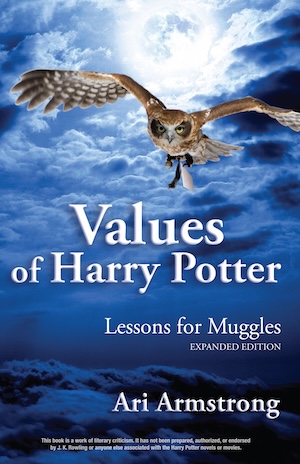

Values of Harry Potter: Lessons for Muggles

This book originally was published in 2011. I published this html version of the book at AriArmstrong.com on December 13, 2025. I retain the copyright. No part of this book may be reproduced elsewhere without my explicit permission. If you wish to help financially support this work, please purchase a paperback or ebook through Amazon, join my Patreon, or donate through PayPal. A quick historical note: When the Potter books first came out, various people on the religious right criticized them because they portrayed witchcraft. Those sorts of criticisms mostly have disappeared as of 2025. Now, Rowling has come under heavy criticism by many people on the left (and even by some people involved in her projects) because of her trans-exclusionary views (I think they are fairly called). At some point maybe I'll address Rowling's views on transgender issues, views with which I largely disagree. Thank you for reading, —Ari Armstrong

[Page numbers matching the printed version appear in subscript or in brackets. This book is a work of literary criticism. It has not been prepared, authorized, or endorsed by J. K. Rowling or anyone else associated with the Harry Potter novels or movies. Copyright 2008, 2011 by Ari Armstrong.]

Copyright © 2008, 2011 by Ari Armstrong

Ember Publishing, Denver, Colorado

Designed [for print] by Jennifer Armstrong

Armstrong, Ari

Values of Harry Potter: Lessons for Muggles, Expanded Edition

Includes bibliographical information and index

Literary Criticism, Philosophy

ISBN [for trade paperback]: 978-0-9818030-1-2

[Back Cover]

Literary Criticism, Philosophy

"A delightful array of fresh insights into J. K. Rowling's works.... A unique opportunity to explore their core values and discover why we find them so captivating and so inspiring."

—Diana Hsieh [Brickell], author of "Dursley Duplicity" in Harry Potter and Philosophy

The adventure stories of the boy wizard Harry Potter tap life's most pressing questions about love and values, evil, free will, and the soul.

Ari Armstrong's Values of Harry Potter explores the complex themes of J. K. Rowling's beloved novels, illuminating the heroic fight for life-promoting values, the hero's need for independence, and the role of choice in virtue. Drawing on the ideas of Aristotle and Ayn Rand, Armstrong then critiques the Christian elements of self-sacrifice and immortality, arguing that they ultimately clash with the essential nature of the hero as exemplified by Harry Potter and his allies.

Values of Harry Potter offers a unique, succinct, and provocative look at Rowling's revolutionary novels for both enthusiasts and critics. This Expanded Edition also reviews the psychology, government, and news media of the novels.

Ari Armstrong resides in Colorado with his wife Jennifer and their cat Cali. Ari writes for FreeColorado.com, AriArmstrong.com, and, with his father Linn, Grand Junction's Free Press.

Cover design by Jennifer Armstrong

Note on the Ebook

[This ebook version of Values of Harry Potter contains the identical text of the trade paperback, except that page numbers matching the paperback are inserted in subscript or in brackets, and select notes are added in brackets. The chapter titles listed on the Contents page are hyperlinked to the chapters themselves, and the chapter titles within the text link back to the Contents. Endnote markers and the endnotes link back and forth. Select endnotes and references link to outside documents. Notes regarding the Harry Potter novels are listed separately, and, where relevant, page numbers link to the appropriate section of those notes. Page references in the index link to the relevant pages, though there's no way to link back to the index entries from within the text.]

[Page 5]

Contents

Acknowledgments · 7

Introduction: The Magic of Harry Potter · 9

Part I: Lessons of Harry Potter

Chapter One: The Heroic Fight for Values · 14

Chapter Two: Independence: Mark of the Hero · 28

Chapter Three: Free Will: "It Matters Not What Someone Is Born" · 51

Part II: Criticisms of Harry Potter

Chapter Four: The Clash of Love and Sacrifice · 71

Chapter Five: Materialism and Immortality · 86

Conclusion: Mischief Managed · 96

Part III: Additional Essays · 99

The Psychology of Harry Potter · 100

Wizard Law and Segregation · 115

News Media in Harry Potter · 120

Beedle the Bard Expands Rowling's Moral Themes · 131

The Fading Magic of Tolkien and Alexander · 139

Harry Potter's Lessons for Muggle Politicians · 143

Why Potter Fans Should Read Ayn Rand · 146

Reflections on Films Six and Seven · 149

Notes · 155

Index · 169

[Page 7]

Acknowledgments

I might first acknowledge the clever fans of the Harry Potter series who have made it a phenomenon; submitting this modest book for their review makes me feel a bit like Hermione preparing for an O.W.L. Readers are welcome to send me comments about the book at www.ValuesOfHarryPotter.com [deprecated], where I'll reply to select comments and publish additional articles.

Numerous reviewers offered helpful advice and criticism. My editor, Melissa Holt, reviewed the manuscript with the exactness of Minerva McGonagall. Jennifer Armstrong, my wife, examined drafts at every step, lent me moral support, and designed every aspect of the book; the project would not have been possible without her loving assistance. (Jennifer, a redhead, would be at home in the Weasley household, though she'd have to work on her Quidditch skills.) After looking at very early drafts of the material, Lin Zinser also reviewed the entire manuscript. Darla Graff offered penetrating and detailed notes on most sections that dramatically improved them. Ed Peters double-checked factual claims and citations and also offered general feedback. Craig Biddle, Diana Hsieh, and Brian Schwartz reviewed early drafts of material that eventually became parts of Chapters One, Four, and Five, and Diana also offered useful comments on free will. An anonymous reviewer provided helpful feedback on parts of Chapters One and Four. Readers ought not blame any reviewer 8 for faults in this book, because I stubbornly resisted some of the reviewers' suggestions, and I alone approved the final manuscript. Any remaining errors, whether in fact or logic, are solely my own.

Finally, I thank J. K. Rowling for writing the books that have fascinated and inspired millions of readers around the world and will continue to do so as long as children and youthful spirits yearn for a little magic in their lives.

[Page 9]

Introduction: The Magic of Harry Potter

It was the most exciting book buy of my life. My wife and I, along with several family members, went to a bookstore on the evening of July 20, 2007, when stores stayed open late so that they could sell the final Harry Potter novel starting at midnight. Never have I seen any bookstore so packed or heard one so noisy. Gangs dressed as Quidditch players passed by on the sidewalk. Innumerable foreheads sported lightning marks. Children and adults alike drew lots for a place in line to buy the book. The scene was similar in countless bookstores across the nation.

There is no question that J. K. Rowling's Harry Potter books constitute an unprecedented global literary phenomenon. Scholastic, publisher of the books in the United States, announced that the last book sold 8.3 million copies within the first twenty-four hours and 11.5 million in ten days. Combined, the books have sold over 350 million copies worldwide.1 A Harris Poll suggested that, while the Bible is the favorite book among U.S. readers, "the second choice for 18- to 31-year-olds was J. K. Rowling's Harry Potter series."2

Nor does anyone doubt Rowling's profound impact on the reading habits of children. My young cousins, for example, voraciously read each book several times. Parents credit the 10 books for inspiring their children to do better in school.3 British Chancellor Gordon Brown said, "I think J. K. Rowling has done more for literacy around the world than any single human being."4 It's difficult to accuse him of exaggeration, if we limit consideration to the modern era.

Yet fierce debate rages over the books. At one end some claim that "the signature of the Prince of Darkness is in these books.5 In the documentary Jesus Camp, a woman speaking to a group of children says, "Had it been in the Old Testament, Harry Potter would have been put to death."6

The Vatican has offered a mixed review. Before he became Pope, Joseph Ratzinger warned Catholics to beware the books' "subtle seductions," according to Catholic News Service. More recently, the source reported, "The Vatican newspaper sponsored a face-off between a writer who said the Harry Potter novels offer lessons in the importance of love and self-giving and one who said they teach that with secret knowledge one can control others and the forces of nature."7

Obviously, I'm a Potter fan.

I came late to the series, starting after someone gave my wife the first four books in a paperback boxed set. I hold no particular interest in fantasy, and I dismissed Potter as books for kids. But several of my adult friends continually raved about the books, so I thought I'd give them a try.

Quickly I was hooked. What first struck me was the richly dark world of Harry's childhood with his aunt and uncle, Petunia and Vernon Dursley. The idea of escaping from such dreadful circumstances into a bright world of magical heroes fascinated me; it made me think of all the real boys and girls who grow up in similarly bleak circumstances (or worse) and struggle to create a better life for themselves. I hoped that the Potter books comfort those children and motivate adults to help them. Then Rowling took me into an adventure that I enjoyed but did not fully appreciate until I had read further into the series.

By the end of the first book, my respect for the series was sealed with a couple of outstanding quotes by Professor Albus 11 Dumbledore. "Fear of a name increases fear of the thing itself." "It takes a great deal of bravery to stand up to our enemies, but just as much to stand up to our friends." Yet I was intrigued by some of Dumbledore's other comments that struck me as cryptic. "To the well-organized mind, death is but the next great adventure." "Humans do have a knack of choosing precisely those things [as much money and life as you could want] that are worst for them." "Your mother died to save you." What did Dumbledore mean by these comments? What did they portend for the rest of the series?

Through the first three books, I continued to think of Harry Potter as interesting children's books. Then I read the fourth book, Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire. The main plot, at least until the last few chapters, remains oriented toward children; it involves Harry meeting several challenges in a contest, such as taking an egg from a dragon. More mature themes take on greater significance: the characters deal with bigotry and slavery, the laws of society, and the ethics of journalism. Near the end of the book the forces of evil rise to strength. These are not themes for children, but for maturing youth and adults. The final three books excite youthful spirits, yet the themes grow more complex and at times quite dark, as the villain Lord Voldemort combines qualities of Satan and Hitler.

My book focuses on the heroic fight for values in the Harry Potter series. Harry Potter and his allies struggle valiantly to defend the things that matter to them—their friends, their lives, and their liberty. They do so against great odds, often in agonizing circumstances, and against powerful and relentlessly vicious enemies.

In Chapter One, I review examples illustrating the central theme of the heroic valuer, as contrasted with the motives of the villains.

Chapter Two reviews independence, the virtue that allows the heroes to discover the values that enhance their lives and to pursue them with thoughtful courage.

In Chapter Three, I discuss free will in Harry Potter, the precondition of the selection and pursuit of values.

12 Chapter Four grows more critical, arguing that Rowling's theme of the heroic valuer ultimately clashes with her secondary theme of Christian self-sacrifice.

Finally, Chapter Five addresses the theme of immortality. How does the quest for earthly immortality motivate the villains? What is the connection between the fear of death, an obsession with objects, and the abuse of others? What does this have to do with the Horcrux? Does virtue require a belief in supernatural immortality? I argue that Rowling does not convincingly develop her theme of immortality or connect it to the motivation of the heroes.

This book presupposes that readers are familiar with the Harry Potter books. The pages that follow discuss crucial elements of plot and will ruin the suspense of the books for those who haven't yet read them.

Much of the fighting over the Potter books involves Christians on both sides, and two of my chapters explicitly deal with Christian themes. Though I am not Christian, and I criticize religion in other forums, I acknowledge that Rowling intentionally includes Christian themes in her books, and I want to understand them correctly. I argue that Rowling's Christian themes of sacrifice and immortality clash with her more central theme of the heroic valuer. I develop my case from the books and outside sources.

My take on the Christian elements of the Potter books conflicts with the perspective of other reviewers. Some argue that the books should be avoided because they oppose Christianity. Others argue that the books should be read and praised because they promote Christian themes. My claim is that the Christian elements of the Potter books are real but disconnected from the broader moral themes of the books, which nevertheless remain brilliant (as Ron Weasley might say).

I compare and contrast some of Rowling's ideas with those of Ayn Rand and Aristotle. Rowling and Rand treat both independence and free will in some strikingly similar ways. Regarding sacrifice, the views of Rowling and Rand clash. On that topic I rely heavily on the writings of Aristotle, whose comments 13 may seem surprising only because they are too often neglected. Rowling and Rand both create vivid heroes who fight for their values, and they again clash on immortality, yet those themes are common enough that I found direct comparisons unnecessary.

Part of my motivation for writing this book is the conviction that the moral lessons of Harry Potter are profoundly important. I made some regrettable moral mistakes as a young adult because I failed to heed some of these lessons, which were widely available long before Rowling conceived Harry Potter. It is vitally important to understand one's values, choose the right values, and enact the virtues that make the achievement of values possible.

While I appreciate Rowling's contribution to a renewal of literacy, I am desperately grateful to her for promoting moral literacy. Adopting the virtues portrayed by the heroes of Harry Potter can make you a better person. Yes, read the books for the sheer joy of the heroic, magical adventure. Then think more deeply about the moral lessons of Harry Potter and strive to integrate them in your day-to-day life. Part of the point of admiring heroes is to become a hero. It's not enough to read about it or write about it; we, all of us, need to live it and face that challenge every day. That is how to discover the true magic of Harry Potter.

Chapter One: The Heroic Fight for Values

Why have J. K. Rowling's books attracted such a devoted following? Much of the success has to do with the vivid alternate reality that Rowling has created with her magical world. Seldom does a reader encounter such richly developed characters; it's hard to read the books and not imagine sitting up in the towers, plotting with Harry Potter or cracking jokes with the Weasley twins. This is particularly true given that Rowling's magical world is written to coexist with our own; readers are tempted to look twice when they see eccentrically dressed people walking down the street who just might be wizards in disguise.

Rowling also has crafted a stunningly intricate plot spanning thousands of pages. While each book contains its independent story, the books also bind together in a grand epic that (including flashbacks) spans decades. Rowling plants deep connections between the books that inspire multiple readings—to take one early example, Hagrid rides into the series on a motorcycle borrowed from Sirius Black, whom we do not meet for another two story-years.

Then there are the subtle references to external works and events ranging from ancient mythology to Christian theology to World War II. Even the names of the characters and the language of the spells provoke research and speculation.

15 Yet the phenomenal and enduring appeal of the books is due to something more fundamental. What do I remember most vividly about the books? The moments when Harry makes the choice not to put his head down but to face terrifying threats to the people and the life that he loves. Each book reveals such moments.

Harry Potter offers one of literature's great examples of the virtuous hero fighting against the most vicious form of evil. Yes, the vivid storytelling, the intricate plot, and the many layers of allusions place Rowling's series among the grandest and most exciting of epics. But in addition to these elements Rowling does something else particularly well—she shows in passionate detail why victory matters so very much to the heroes.

The overriding theme of the Harry Potter books is the heroic, courageous fight for values. Harry loves his life, loves his friends, loves the magical world in which he lives—and refuses to let go of those values without fighting with all of his strength and resolution.

The budding romances, the school dance, the friendly chats in the halls, the studying and tests, the family dinners, the sports matches—these are not diversions from the central story; they are the reasons why the fight against Voldemort matters. They are the moments of enjoying friends and setting one's course in life. The small moments are not themselves central values, but collectively they manifest such values. Without the heroes' passion for their values expressed in day-to-day living, the stories' detail, plot, and references amount to little.

Harry and his allies feel fear, they suffer pain, and yet always they rise to defend what is important to their lives. They do not ignore the warnings or turn their gaze away; they recognize real dangers to their values and struggle valiantly to overcome those threats.

Harry Potter shows that one must always fight for one's central values, which give life meaning and for which life itself may be risked. Through Harry Potter, Rowling inspires millions of readers to live their lives completely and never willingly surrender their own values.

16The Values of the Heroes

What are the central values that Harry and his allies fight to defend?

To grasp why Harry holds his values so intensely, first recall how miserable he is before entering the magical world. Harry is able to see a deep contrast between a life lacking values and a life filled with them.

Until he enters the magical world, Harry lives a deprived life with his awful uncle and aunt, Vernon and Petunia Dursley, and their dreadful son Dudley. The elder Dursleys hated Harry's magical parents, about whom they do not tell him. They resent his magical potential and hide it from him. They underfeed him and force him to sleep beneath the stairs, while spoiling their bratty and manipulative son in equal proportions. "The Dursleys often spoke about Harry...as though he wasn't there—or rather, as though he was something very nasty that couldn't understand them, like a slug." Dudley, picking up his parents' prejudices, leads a little gang in "Dudley's favorite sport: Harry Hunting." Because "Dudley's gang hated that odd Harry Potter in his baggy old clothes and broken glasses," and because the gang terrifies the rest of the students, Harry is friendless at school.

Yet Harry remains open to a life filled with values, and he begins to realize such a life when, on his eleventh birthday, he receives a letter notifying him that he is a wizard who has been accepted into the Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry. This opens up a new world for Harry—one in which he is able to discover and actively pursue opulent values.

Even before reaching his new school, Harry finds excellent friends whom he values immensely. Hagrid, the gamekeeper of Hogwarts, delivers Harry's letter of acceptance, offers him heartfelt kindness and gifts, and tells Harry about the wizarding world and his past, including Voldemort's murder of his parents. Harry forms a deep, lasting friendship with Hagrid.

Next Harry meets the Weasley family when Molly, the mother, helps him get onto the train platform for the Hogwarts Express. 17 The twins, Fred and George, help Harry load his trunk onto the train. And Ronald, with whom Harry shares a train car, becomes Harry's best friend. Eventually the Weasleys practically become Harry's adoptive family. Harry goes on to find many other friends at Hogwarts and among the broader magical community.

Harry soon finds a new home at Hogwarts. He discovers and develops his natural talents, such as flying by broomstick and performing defensive spells. He turns his skills with a broom into success on the Quidditch field. Harry enjoys many of his classes (if not all of them), and he values honing his magical skills and learning extracurricular lessons from Hogwarts.

Harry never takes for granted the things and people that matter to him. Because Harry deeply values his school and friends (and remembers his miserable life before them), he defends these values passionately.

Here we consider three main examples illustrating the basic motives of the heroes, to start with obvious cases that establish the theme before moving on to more difficult examples. (In Chapter Four, where I discuss Christian sacrifice, I review cases in which the heroes' motives are ambiguous and difficult to parse.)

In his first year at Hogwarts, Harry faces the first serious threat to his values. Voldemort, Harry learns, is attempting to steal the Philosopher's Stone (unfortunately called the Sorcerer's Stone in the American editions), which would allow Voldemort to regain his power. Harry's commitment to his values does not waver in the face of danger; Harry decides to try to stop Voldemort.

In persuading his closest friends Ron Weasley and Hermione Granger to join him, Harry points out:

Voldemort's coming back! Haven't you heard what it was like when he was trying to take over? There won't be any Hogwarts...He'll flatten it, or turn it into a school for the Dark Arts! ...D'you think he'll leave you and your families alone...? If I get caught before I can get to the Stone, well, I'll have to go back to the Dursleys and wait for Voldemort to find me there, it's only dying a bit later 18 than I would have, because I'm never going over to the Dark Side! ...Nothing you two say is going to stop me! Voldemort killed my parents, remember?

Harry acts to defend his own life and everything that is important to his life: his liberty, his school, and his friends and other innocents.

Harry's attempted rescue of his godfather Sirius Black in Order of the Phoenix again shows Harry courageously defending his values. Harry rushes to save Sirius from Voldemort because Harry loves Sirius. Sirius was best friends with Harry's father and knew Harry as an infant, and he shows deep commitment toward Harry as his godfather. Sirius wishes he could offer Harry a better home, even though he himself must go into hiding. He gives Harry love, fatherly advice, and meaningful gifts, such as Harry's prized flying broomstick. They almost become as father and son.

Near the end of Order of the Phoenix, Harry believes, "Sirius is trapped...Voldemort's got him, and no one else knows, and that means we're the only ones who can save him." Harry sets out to save the life of a loved one from Voldemort.

Harry's actions, then, are understandable, but why do his friends—Ginny and Ron Weasley, Hermione, Luna Lovegood, and Neville Longbottom—join him on the dangerous mission to rescue Sirius? They too love their friends and understand the threat that Voldemort poses to all of their values. We look briefly at the motives of each friend in turn.

Ginny has a particular interest in protecting Harry. Aside from her loyalty and affection toward Harry since he saved her life by rescuing her from the monster's den in Chamber of Secrets, she has always held a crush for him, which later develops into romance. Ginny too regards Sirius as a friend. And Ginny, who was possessed and nearly killed by Voldemort, knows in a deeply personal way the mayhem that Voldemort threatens to unleash upon her world.

Luna joins Harry because she deeply cares for him and wants to protect her friends from Voldemort. Luna, an eccentric young lady with few friends, holds dear her few excellent companions. 19 While Luna also recognizes the broader threat that Voldemort poses, perhaps her deepest concern is for the safety of these particular friends, who mean the world to her. It is only later, when Harry learns that Luna has been kidnapped, that he fully appreciates how much Luna values her friends—she has lovingly painted highly detailed portraits of them.

Neville joins Harry because, perhaps more than any of the other friends, he understands Voldemort's destructive potential and knows the villain must be stopped. Like Harry, Neville suffered great personal loss at the hands of Voldemort, whose followers tortured Neville's parents to insanity. Neville, too, recognizes Voldemort's power to destroy his values.

Moreover, Neville regards Harry as a dear friend as well as a critical ally in the fight against Voldemort, so Neville wants to keep Harry safe. Harry has always looked out for Neville. Even though Neville is at times socially awkward, Harry stands up for him against the school bully, Draco Malfoy, during their first flying lesson. Later, when Draco places a curse on Neville, Ron encourages, "You've got to stand up to him, Neville!" In response to Neville's concern that he's not brave enough, Harry says, "You're worth twelve of Malfoy." When Draco tells Neville he's "got no brains," Neville invokes Harry's words against Draco and joins Ron in fighting him. Neville, then, helps Harry because he values him tremendously as a friend. Neville also realizes that Harry holds power against Voldemort and therefore is an invaluable ally who must be protected.

Ron and Hermione stand by Harry as they have in the past. The friends hate Voldemort and want to thwart him, and they value Harry as a brave, virtuous, and loyal companion. Recall, for example, that early in their first year, Harry and Ron rush to rescue Hermione from an escaped troll. The three develop a very deep love for each other as friends and thus are prepared to do whatever it takes to protect each other from harm. It is no surprise that his friends join Harry on a dangerous mission to save Sirius and, later, to battle against Voldemort. Each has a personal stake in the outcome.

20 Outside of Harry's schoolmates, Dobby, a house-elf, offers another clear example of a character who fights to protect what is dear to him. Why does Dobby put himself at great personal risk and incur painful injuries to help Harry throughout the books?

House-elves have been forced into slavery and are used to being treated viciously. Dobby held Harry as a hero even before the two met, Dobby explains, because the infant Harry defeated Voldemort and now stands against his return to power:

Ah, if Harry Potter only knew...what he means to us, to the lowly, the enslaved, we dregs of the magical world! Dobby remembers how it was when [Voldemort] was at the height of his powers, sir! We house-elfs were treated like vermin, sir! Of course, Dobby is still treated like that...But mostly, sir, life has improved for my kind since you triumphed over [Voldemort]. Harry Potter survived, and the Dark Lord's power was broken, and it was a new dawn, sir, and Harry Potter shone like a beacon of hope for those of us who thought the Dark days would never end.

Thus Dobby goes out of his way to protect Harry, and he continues to find new reasons to regard Harry as his dearest ally. Early in Chamber of Secrets, Dobby tries to sabotage Harry's efforts to return to school in order to protect Harry from Dobby's malicious master, Lucius Malfoy (Draco's father). The magical bonds of slavery force Dobby to hurt himself for this. At their first meeting, Harry politely asks Dobby to sit on his bed. Dobby "burst into tears," explaining, "Dobby has never been asked to sit down by a wizard—like an equal." Later, when Harry tricks Lucius into freeing Dobby from his service to the Malfoys, Dobby recognizes the great deed Harry has done for him.

By the final book, Dobby becomes a central hero of the series when he rescues Harry and his friends from the clutches of Voldemort's followers—again putting himself at risk and this time falling on the tragic side of luck. Yet to Dobby the risk was worth 21 it, for in defending Harry Potter and his allies, Dobby defends everything that is good about his own life.

The Villains

It is clear that Harry Potter and his allies generally act to defend their personal values. What, then, motivates the villains of the story?

Slytherin is one of the four Hogwarts houses named after the founders of the school. Before placing students in their houses, the Sorting Hat describes Slytherin, through which Voldemort and most of his followers passed, as "cunning folk [who] use any means / To achieve their ends." Before placing Harry in Gryffindor, the house known for bravery, the Sorting Hat tells Harry that "Slytherin will help you on the way to greatness, no doubt about that."

However, the villains do not, in fact, attain greatness, nor do they achieve any ends worth wanting. While Harry and his allies heroically defend the values dear to them, all the villains achieve is misery and self-destruction.

In the first book, Professor Quirrell, who has been secretly working to help Voldemort recover the Philosopher's Stone, tells Harry: "There is no good and evil, there is only power, and those too weak to seek it." Yet Quirrell admits that he fares poorly under this sort of power. He says, shivering, "[Voldemort] has had to be very hard on me. ...He does not forgive mistakes easily. When I failed to steal the stone [previously], he was most displeased. He punished me."

In the case of the Philosopher's Stone, who has actually achieved life-enriching values? On one hand, Harry and his friends undertake a difficult, risky, and painful quest to prevent Voldemort from gaining the Stone—in order to protect all that they cherish. Quirrell, on the other hand, has made himself the servant of a vicious wizard who tortures him, alienating himself from all love, friendship, and other requirements of genuine happiness. It is Quirrell who destroys all of his potential values, surrendering not only his mind but his physical body to Voldemort. Quirrell serves as the bodily host for Voldemort's twisted soul, which is all that 22 remains after the wizard's prior defeat. Ultimately, Voldemort "left Quirrell to die."

Prisoner of Azkaban reveals a similar example. Harry's godfather Sirius, long imprisoned for a crime he did not commit, confronts Peter Pettigrew, the man who betrayed Harry and his parents to Voldemort. Sirius accuses: "You never did anything for anyone unless you could see what was in it for you. ...You'd want to be quite sure [Voldemort] was the biggest bully in the playground before you went back to him, wouldn't you?"

The cowardly Pettigrew eventually admits his vile deeds. He offers an excuse: Voldemort "was taking over everywhere! ...What was there to be gained by refusing him?"

Sirius answers him: "What was there to be gained by fighting the most evil wizard who has ever existed? ...Only innocent lives, Peter!" Pettigrew responds, "You don't understand! ...He would have killed me, Sirius!" Sirius is unsympathetic: "Then you should have died! Died rather than betray your friends, as we would have done for you!"

Is it true that Pettigrew gains personally by turning over his friends to Voldemort? Pettigrew loses all of his friends to prostrate himself before a vicious master. With Voldemort's initial defeat, Pettigrew must transform into a rat and live that way for years. Once he rejoins Voldemort, he lives in a state of perpetual terror. Voldemort, in regaining his body, forces Pettigrew to chop off his own hand for use in the transformation. As Voldemort toys with the mortified Pettigrew, the traitor is reduced to "uncontrollable weeping." Voldemort finally gives him a new hand—which later strangles him to death. Pettigrew exchanges all of his values for a pitiful and brief existence of misery, isolation, terror, pain, and servility.

Had Pettigrew tried to resist Voldemort, Dumbledore's supporters, the Order of the Phoenix, might have been able to protect him. Pettigrew could have fought against Voldemort, increasing the chances of taking him down earlier. If Voldemort killed Pettigrew—as he does in the end anyway—at least Pettigrew could have died fighting for values that gave his life meaning. 23 What Pettigrew tragically fails to realize, as Sirius succinctly states later on, is that "there are things worth dying for." That is, there are things worth risking one's life to defend—because life without them isn't worth living.

Another example of the self-destructiveness of following Voldemort comes from Half-Blood Prince, in which Draco Malfoy's mother, Narcissa, visits Professor Severus Snape. Narcissa believes that Snape too is loyal to Voldemort, but Snape is actually working as a spy for Dumbledore, whom Voldemort has ordered Draco to murder. Narcissa rightly believes that Voldemort assigned Draco this impossibly dangerous task so that he would be killed in the process of attempting it. Voldemort does this to punish the elder Malfoys for failing to carry out one of Voldemort's previous plans. Narcissa asks Snape to help Draco. "My son...my only son," she pleads. Snape replies, "The Dark Lord is very angry...You know as well as I do, Narcissa, that he does not forgive easily." Serving Voldemort poses a threat to one's own life and every value that promotes it.

Indeed, even to give Voldemort bad news can be a death warrant. When he learns that Harry has stolen an object that contains a piece of his soul, Voldemort takes out his rage on several of his followers, including Lucius Malfoy and Bellatrix Lestrange, who is Voldemort's most loyal surviving supporter. The pair barely escape with their lives, while "those who were left were slain, all of them, for bringing him this news."

What about Voldemort himself? Does he live a happy life enriched with values? Dumbledore tells Harry that, even as a youth, Voldemort had "obvious instincts for cruelty...and domination. ...Lord Voldemort has never had a friend." While Harry's life is filled with friends and loved ones, Voldemort's life is devoid of such values.

Moreover, Voldemort performs horrendous acts of evil, twisting his soul beyond recognition as human. When Voldemort slays a unicorn to drink its sustaining blood, he achieves only "a half-life, a cursed life," as a centaur explains to Harry. Voldemort commits many murders, and as Harry learns, Voldemort's dark magic leads 24 to a depraved existence worse than death. Killing "is an act of violation...Killing rips the soul apart." Dumbledore notes that "Lord Voldemort has seemed to grow less human with the passing years," his soul "mutilated beyond the realms of...'usual evil.'"

Nor does Voldemort ultimately achieve the power over others that he seeks. After his power is destroyed by the infant Harry, Voldemort lives a shadowy existence, barely alive. When he regains his power, much of the wizarding world again fights against him, trying desperately to destroy him. Finally, Harry and his allies succeed in the task.

Voldemort and his followers abuse and seek to control others, and in doing so they undermine their own life-promoting values. Harry and his allies fight for and usually achieve a life filled with joy, happiness, friendship, love, and worthwhile pursuits. Voldemort and his followers achieve for themselves pain, suffering, fear, alienation, and in many cases death.

The contrast between the heroes and the villains illustrates the nature of values. At the simplest level, values are the things a person goes after and wants to get, achieve, or protect. However, such a limited concept doesn't explain the differences between Harry and Voldemort. If Harry values friends, his liberty, a pleasant meal, Quidditch, and his wand, Voldemort values power and inflicting pain. In the broader sense, values must genuinely contribute to one's life, and they must be attainable without destroying the rest of one's values. Friendship in fact contributes to Harry's well-being and happiness and supports his other values. Inflicting pain in fact makes Voldemort a despicable wretch who systematically destroys everything that makes life worth living. In the broad sense, then, a value is not merely something that one goes after; it is something worth going after. I refer to values in that broad sense.

Values in the Face of Death

Harry Potter and his allies fight for their values, while the villains act to destroy their own values. This basic theme of Harry Potter illuminates more difficult cases.

25 At times the heroes put their lives at extreme risk. However, generally they do so in order to defend their own values. Risking one's life for one's values is the ultimate form of fighting for values. While nobody hopes to be placed in such circumstances—and while, thankfully, they are extremely rare in the free world outside of wartime—when a life-threatening danger emerges, the heroic valuer finds the courage to confront the danger.

The books revolve around three momentous acts in which characters put their lives on the line. When Voldemort attacks the infant Harry, Lily gives her life to save her son, and this is the "ancient magic" that first defeats Voldemort. In Half-Blood Prince, Dumbledore gives his life to save a student and protect Snape (who is working undercover against Voldemort). In the final book, Harry offers his life to save his friends and destroy Voldemort. Let us consider these examples in turn.

Voldemort kills Harry's mother because he hears of a prophecy that predicts a newborn boy will grow up to threaten his power. Voldemort intuits that this boy is Harry, the son of James and Lily Potter. Voldemort murders James and Lily and attempts to murder Harry. Lily dies protecting her infant son.

Dumbledore explains to Harry why Voldemort could not kill him as an infant and why Harry continues to find protection with his mother's family. "You [are] protected by an ancient magic...I am speaking, of course, of the fact that your mother died to save you. She gave you a lingering protection...that flows in your veins to this day. ...Her blood became your refuge."

Any decent parent, and anyone who has seriously contemplated parenthood, recognizes the supreme value that is one's own children. Lily loves her son more than anything, and she does what any normal parent would do: she tries to protect her child from a murderer. Lily begs Voldemort, "Not Harry, please no, take me, kill me instead." Voldemort "could have forced her away from the crib, but it seemed more prudent to finish them all."

Even if Lily had not tried desperately to save the life of her son, she still would have been killed. Had she escaped Voldemort 26 on that night, her life would have been in constant danger, as Voldemort is a ruthless killer.

More importantly, if Lily had failed to take every possible action in defense of her son, her highest value, she would have lived in constant agony had she lived and Harry died. For her own sake, Lily had to defend Harry. Even though the effort appeared hopeless, the alternative was unthinkable. Only one choice was open to Lily with any conceivable chance of protecting her values.

Dumbledore's death, the second major example, is described near the end of Half-Blood Prince. When Draco confronts Dumbledore with the intention of killing him, Dumbledore recognizes that Voldemort has threatened to kill Draco and his entire family should he fail. Finally, Draco cannot bring himself to kill his headmaster. Dumbledore begs Snape to do it instead.

Dumbledore takes this extreme action to protect his values. As headmaster of Hogwarts, Dumbledore has pledged himself to the instruction and safety of his pupils, and Draco, a troubled young man but not one beyond hope, remains one of Dumbledore's students. Dumbledore is committed to his work—his work is his life—and he could not bear to allow Draco's soul to be "ripped apart" through an act of murder. By allowing Snape to kill him, Dumbledore not only protects Draco from spiritual destruction and certain death at the hands of Voldemort, but also maintains Snape's role as a spy, enabling Snape ultimately to help bring down the vicious tyrant.

What are Dumbledore's alternatives? Dumbledore is severely injured, and it is unclear whether he could have successfully fought Voldemort's followers even if he had tried. Dumbledore knows that, by failing to protect Snape's role as a spy, the world that he values likely would continue to crumble around him. Moreover, when Dumbledore asks Snape to kill him, he knows that, owing to a previous injury, he has only months to live anyway. Dumbledore chooses a moment's satisfaction knowing that he is protecting Draco, Snape, and the rest of his values. His alternative is to betray the role of headmaster that he loves and then spend several months of physical and emotional agony as his body and entire world fall apart.

27 Turning to the final case, Harry apparently must die because, as Dumbledore explains to Snape, when Voldemort tried to kill Harry "a fragment of Voldemort's soul...latched itself onto" him. "And while that fragment of soul...remains attached to and protected by Harry, Lord Voldemort cannot die." Upon hearing this, Harry believes that "he was not supposed to survive." Harry, thinking that Voldemort will live so long as Harry does, marches off willingly to meet his death.

What is the alternative? So long as Voldemort lives, neither Harry nor any of his loved ones are safe. His choice is death, knowing in the process that his action will save everyone else he loves, or the likelihood of a short and painful life during which he gets to watch his loved ones murdered around him. Notably, Harry does not put his life on the line for his enemies or even for nameless strangers, but rather for his friends and allies; when contemplating his fate he remembers a kiss with his beloved.

Moreover, Harry does not die but rather kills off the part of Voldemort's soul trapped inside of him (by surviving Voldemort's curse) so that he can finally defeat the monster. Dumbledore suspected all along that Voldemort would not really be able to kill Harry, again because of the protection of his mother's final act of love. Even though Harry was convinced he was headed for death, the event shows that such courageous actions can succeed. Though Harry's success in the story is facilitated by magic, his success mirrors real-world cases of courageous triumph in the face of seemingly overwhelming odds.

It is precisely because Rowling shows vivid characters fighting tenaciously for their values that her books are so compelling. Her books will inspire generations of readers to reach for the strength and moral courage to defend the values that make their lives worth living.

Now that we have explored the central theme of the heroic valuer, we turn in Chapter Two to a discussion of independence, a virtue necessary for the achievement of values.

Chapter Two: Independence: Mark of the Hero

Among the moral themes of the Harry Potter books is the recognition of the value of independence in thinking and acting. Independence in this context means relying upon one's own reasoning mind to reach decisions in consideration of the relevant facts and then acting for values consistent with such judgments. The opposite of independence is to profess beliefs and take actions not because they are true and right, but because of what other people think.

Independence does not mean ignoring others, disdaining them, avoiding their company, or rejecting their help. Indeed, those who think and act independently put themselves in an excellent position to develop valuable relationships with others; the heroes of J. K. Rowling's books develop deep friendships and loyalties. Those who place their minds and values at the mercies and whims of others, on the other hand, tend to relate to others based on social pressures or considerations of status. Thus, independence is not about whether one has friends; it is about whether one approaches all of life, including relationships with others, according to one's own considered judgment of the facts.

Another way to describe independence is thinking and acting in accordance with one's first-handed understanding. Yes, one can 29 learn and gain values from others, but only by reaching one's own honest judgment about such knowledge and benefits.

Second-handers, then, are those who accept claims because of social pressure or status or a misplaced trust in authority. (For the classic treatment of the first-hander versus the second-hander, see Ayn Rand's 1943 novel The Fountainhead.8) An independent, first-handed thinker defies the opinions of crowds and authorities when they contradict known facts and reasoned beliefs.

Second-handers try to gain values as well as knowledge through a misplaced reliance on others. For example, second-handers will claim to want something just because it's popular, or they will try to get something by manipulating or coercing the opinions of others. The independent actor, by contrast, holds first-handed values and seeks to influence others solely by honest persuasion, in accordance with the other person's own independent, first-handed understanding.

Rowling presents many positive examples of independence and many negative examples of second-handedness, which comes in many variants. After considering how second-handers attempt to gain social standing and power in the novels, we will look at the alternative of independence that characterizes the actions of the heroes. The examples provided by the books illustrate the nature and problems of the second-hander as well as the virtues of the first-handed heroes.

Second-Handers and Social Standing

Early in his life, Harry witnesses the second-handed behavior of the Dursleys, who despise the magical and strange Potters. Both Vernon and Petunia orient themselves primarily toward their neighbors.

Vernon becomes enraged merely to see people (wizards, in fact) wearing "funny clothes." When he hears some of these wizards mention Harry's name, he tries to pretend that this can't be his nephew. Vernon hopes he is "imagining things, which he had never hoped before, because he didn't approve of imagination." 30 He tries to wish away anything outside of "normal" behavior, but he disdains wishing or hoping for anything beyond social expectations.9

Meanwhile, Petunia concerns herself with "Mrs. Next Door's problems." Later, "Uncle Vernon, Aunt Petunia, and Dudley had gone out into the front garden to admire Uncle Vernon's new company car (in very loud voices, so that the rest of the street would notice it too)."

When Harry was an infant and still living with his parents, Petunia "pretended she didn't have a sister, because her sister and her good-for-nothing husband were as unDursleyish as it was possible to be." And what does it mean to be "Dursleyish"? It means to conform to the standards and expectations of one's neighbors, to be "perfectly normal." "The Dursleys shuddered to think what the neighbors would say if the Potters arrived in the street."

Unfortunately for the Dursleys' comfortably normal life, Voldemort murders Harry's parents, and the infant Harry goes to live with the Dursleys. How do Vernon and Petunia react to Harry's magical potential? "We swore...we'd stamp it out of him!" To the Dursleys, Harry's ability is an "abnormality." The Dursleys' attitude toward Harry does not change even after Harry enters the magical world; having failed to "squash the magic out of him...they lived in terror of anyone finding out that Harry had spent most of the last two years at Hogwarts."

Squashing the magic out of Harry means giving him as little food and possessions as possible and berating him constantly. Meanwhile, the Dursleys encourage their own son to view possessions as means to show up and manipulate others. Though Dudley's parents shower their son with gifts, Dudley doesn't appreciate these gifts, and he proceeds to destroy them. Dudley does not much enjoy the gifts themselves; he enjoys forcing others to give him more than other people get.

Petunia calls her sister Lily a freak, strange and abnormal. Petunia laments that, for her parents, "it was Lily this and Lily that." A memory from Petunia's childhood reveals the origins of her envy: she, too, wanted to attend Hogwarts and learn magic, 31 but she was not born with any magical ability. Rather than develop her own talents and relationship with her parents, Petunia wanted the opportunities and attention that her sister had. (The books suggest no reason to think that the girls' parents were any less supportive of Petunia, but clearly she wanted the advantages of her sister.) Whether trying to get what her sister has or calling her sister a freak, Petunia focuses on her status in the eyes of other people rather than her own goals and values.

Soon after Harry enters the magical world he meets Draco, another second-hander. Draco, in bragging about his possessions, reminds Harry of Dudley. Draco too sees possessions primarily as symbols of social status. He immediately dismisses Harry's first friend of the magical world, Hagrid, as "a sort of servant." Draco also asks Harry whether his parents are magical. Draco says, "I really don't think they should let the other sort in, do you?"

As Petunia is prejudiced against those who can do magic, Draco is prejudiced against those born of Muggles, or non-magical parents. While Petunia fears that associating with the magical world will reduce her status in the eyes of her "normal" neighbors, Draco holds that associating with Muggles and Muggle-born magical students reduces the status of established magical lines. Both Petunia and Draco judge people according to social status rather than as individuals.

In Chamber of Secrets, Rowling introduces an archetype of the second-hand mentality: Gilderoy Lockhart. This new Hogwarts professor surrounds himself with pictures of...himself. When he first sees Harry at a book-signing event, Lockhart drags Harry in front of the cameras, saying, "Nice big smile, Harry...Together, you and I are worth the front page." This exemplifies the relationship between narcissism and second-handedness: the narcissist is infatuated with his own image as measured by the standards of others.

Lockhart constantly reminds others of his fame, including his many awards. On the first day of class, he gives his students a test covering personal details about himself as revealed in his many books. When Harry must serve detention with Lockhart, 32 the professor has Harry help him answer fan mail. "Celebrity is as celebrity does, remember that," Lockhart says. Yet Lockhart's celebrity is no substitute for real ability.

Lockhart constantly brags about his skills, which he is never able to demonstrate. On one occasion, Lockhart unintentionally removes all the bones from Harry's arm while trying to heal it; another time, he tries to make a snake disappear but only makes it larger.

Finally, Lockhart proves his cowardice in trying to avoid helping to rescue Ginny when she is trapped in the monster's chamber. Harry reminds Lockhart of all the brave things he reported doing in his books. Lockhart admits to Harry, "My dear boy...Do use your common sense. My books wouldn't have sold half as well if people didn't think I'd done all those things. No one wants to read about some ugly old Armenian warlock, even if he did save a village from werewolves."

Shocked, Harry questions, "So you've just been taking credit for what a load of other people have done?" Lockhart admits his lies and then tries to wipe Harry's mind of the conversation. Lockhart fails and in the process removes his own memory, reducing himself to helplessness. Lockhart's case demonstrates the ultimate futility and self-destructiveness of living for the empty approval of others, rather than for one's own authentic knowledge and values.

The Temptation of Second-Handedness

Rowling shows that basically good people, even heroes, can sometimes succumb to second-handedness. The clearest example of this is Remus Lupin, the professor who replaces Lockhart for Harry's third year at Hogwarts.

Lupin is unusual because, as a child, he was bitten by a werewolf, thus becoming one himself. He changes into a wolf a few nights each month, when his bite would turn others into werewolves. Fortunately, he can control his transformations using a magical potion created for this purpose. Though Lupin poses 33 no threat to others (unless unable to take the potion on time), he recognizes that most people will never accept a werewolf as an equal. Once his condition becomes known, Lupin, among Harry's best teachers, resigns from the school to avoid parental outrage over a werewolf teaching their children. Harry and Lupin remain close; Lupin was best friends in school with Harry's father and godfather, and Harry joins Lupin in the Order of the Phoenix, the organization formed to battle Voldemort.

Harry wonders why another member of the Order, Nymphadora Tonks, has fallen into poor spirits. Eventually he realizes that it is because she is in love with Lupin, who initially spurns her attentions because he wants to spare her the problems of being involved with a werewolf. Tonks returns to her usual happy nature when she announces her marriage with Lupin.

Lupin regrets his decision to marry Tonks. Leaving his now-pregnant wife with her parents, Lupin offers to travel with Harry. Lupin claims that Harry's father would have wanted it that way. Harry sees through this pretext. He retorts, "I'm pretty sure my father would have wanted to know why you aren't sticking with your own kid, actually." Lupin replies:

I made a grave mistake in marrying Tonks...Don't you understand what I've done to my wife and my unborn child? I should never have married her, I've made her an outcast! ...You don't know how most of the Wizarding world sees creatures like me! When they know of my affliction, they can barely talk to me! ...Even her own family is disgusted by our marriage, what parents want their only daughter to marry a werewolf? ...And if, by some miracle, [my child] is not like me, then it will be better off...without a father of whom it must always be ashamed!

Harry is unsympathetic. He realizes that Lupin is playing into the irrational prejudices that others hold against him. Harry says, "I'd never have believed this...The man who taught me to fight dementors—a coward." Harry's words sting, but they work. 34 Lupin returns to Tonks. Later, when Lupin announces the birth of his son, he asks Harry to be godfather. Although he succumbs to second-handed thinking for a time, Lupin realizes that he must not put social pressure or the views of others above doing what is right for himself and his family.

Second-Handers and Power

At first glance, those who seek the approval of others and those who seek power over others might seem to be opposites. Approval-seekers grovel for attention and for the favor of others; they prostrate themselves to the views of others. Power-seekers, on the other hand, want to exercise power over others and force others to do their bidding. Yet in both cases, the primary orientation is toward other people. Neither the approval-seeker nor the power-seeker focuses on his own knowledge of what is true and right or on his own achievement of values. Both types of second-handers rely fundamentally on other people; they are basically dependent on the views and position of others.

A good example of a power-seeking second-hander is Percy Weasley, Ron's older brother. Percy is not viciously evil, as are the main villains, yet he creates serious problems for himself and for others—notably, his family—through his preoccupation with political power.

In Harry's second year at Hogwarts, Percy serves as prefect, a student leader of the school. Ron finds him "deeply immersed in a small and deeply boring book called Prefects Who Gained Power." Ron mocks, "Percy, he's got it all planned out...He wants to be Minister of Magic." There's nothing inherently wrong with holding a position of responsibility, political or otherwise. Percy's main motivation, however, is not to find work in which he can enjoy using his talents toward a useful goal, but to find a position that grants him social prestige and command.

Once Percy graduates from school, he enters the Ministry of Magic. When his boss, Barty Crouch, Sr., discovers his house-elf Winky (whom we will consider in more detail later) at the scene 35 of a crime, Crouch punishes the elf even without good evidence that she was involved. Percy defends the move on the grounds of public appearance: "Well, Mr. Crouch is quite right to get rid of an elf like that! ...Running away when he'd expressly told her not to...embarrassing him in front of the whole Ministry...how would that have looked, if she'd been brought up in front of [a board]?" For Percy, the way things appear to others is more important than the truth.

Because Percy places appearance before facts and seeks power, he covers for Crouch even when Crouch stops performing his job. As another of Ron's brothers explains, others in the Ministry of Magic "said Percy ought to have realized Crouch was off his rocker and informed a superior. But you know Percy, Crouch left him in charge, he wasn't going to complain." For the same reason, Percy does not question why the Minister of Magic, Cornelius Fudge, asks Percy to join his office. The same brother intuits the reason: "Fudge only wants Percy in his office because he wants to use him to spy on the family." By this time, the rest of the Weasleys have joined the Order of the Phoenix, while the Ministry of Magic has refused to recognize Voldemort's return to strength. Because Percy is a second-hander, all he accomplishes (besides alienating his entire family and his virtuous friends) is to impede the fight against Voldemort.

Percy is not the only member of the Ministry of Magic preoccupied with power and appearance. Fudge, the Minister, chooses to ignore the abundant evidence of Voldemort's return to power and his attempts to assert control over the wizarding world.

Dumbledore warns Fudge that he must take immediate action to counter Voldemort. Fudge refuses to believe the facts. Instead, Fudge accuses, "It seems to me that you are all determined to start a panic." Fudge is more concerned about public reaction to the news than whether the news is true.

Dumbledore tries in vain to get Fudge "to send envoys to the giants" before Voldemort can bring them to his side. Fudge responds: "If the magical community got wind that I had approached the giants—people hate them, Dumbledore—end of my career." 36 Dumbledore returns: "You are blinded...by the love of the office you hold, Cornelius!" Dumbledore also points out to Fudge that he panders to and adopts common prejudices: "You place too much importance...on the so-called purity of blood!" Fudge weakly calls Dumbledore's warnings "insane." Fudge cannot see past his second-handed orientation toward the perception of others. For Fudge, all that is important is that he remain in power and not disrupt popular opinions, however misguided they might be.

In his desperation to cling to power, Fudge only becomes more paranoid—and more dangerous. Before Harry enters his fifth year, Fudge "absolutely refus[es]" to believe that Voldemort has returned to strength. Why? Arthur Weasley, Ron's father, explains, "You see, Fudge thinks Dumbledore's plotting to overthrow him. He thinks Dumbledore wants to be Minister of Magic." Ridiculously, Fudge believes that all of the claims about Voldemort are part of a conspiracy to undermine his authority and position.

What's more, in order to suppress the truth about Voldemort, Fudge turns to censorship. Lupin tells Harry that "the Ministry's leaning heavily on the Daily Prophet not to report any of what they're calling Dumbledore's rumor-mongering, so most of the wizarding community are completely unaware anything's happened, and that makes them easy targets for" Voldemort's followers.

The effort to control the opinions of others through deception is a different twist for the second-hander. Vernon Dursley accepts the beliefs of his neighbors as an absolute and deceives himself to bring his own beliefs into line with those of others. Fudge does the same thing in some situations, but here his lust for power drives him not only to deceive himself but also to try to control the opinions of others and bring popular attitudes into line with his own.

Fudge and the Order contrast sharply. Dumbledore and his allies seek to persuade others through facts and reason so they can understand firsthand the danger Voldemort poses. Fudge tries to manipulate his own beliefs and the beliefs of others. Harry and his allies hold facts as primary. Fudge places opinions before facts.

37 The first-hander seeks to bring his beliefs into line with the truth and with legitimate values. The second-hander treats facts and values as a matter of others' opinion. Whether second-handers try to conform to or manipulate the opinions of others, the second-hander's primary concern is the beliefs of other people, without regard for the legitimacy of those beliefs.

Because Fudge refuses to accept facts, he creates a political environment of fear, intimidation, and caprice. At a hearing intended to silence Harry through trumped-up charges, Fudge falsely calls Harry a liar. Dumbledore reminds Fudge that "the Ministry does not have the power to expel Hogwarts students" or "to confiscate wands until charges have been successfully proven." Fudge retorts, "Laws can be changed."

Unsurprisingly, Fudge's paranoia, refusal to acknowledge facts, and incompetence eventually cost him his job, once Voldemort's return becomes too obvious for even him to ignore. Fudge's replacement, Rufus Scrimgeour, handles the job with greater skill, but he, too, tries to manipulate the opinions of others. Scrimgeour tells Harry:

It's all perception, isn't it? It's what people believe that's important. ...They think you are quite the hero...You might consider it...almost a duty, to stand alongside the Ministry, and give everyone a boost. ...If you were to be seen popping in and out of the Ministry from time to time...that would give the right impression.

Harry sees through Scrimgeour's flattery: "So basically...you'd like to give the impression that I'm working for the Ministry?" Harry throws the offer in Scrimgeour's face:

You see, I don't like some of the things the Ministry's doing. Locking up Stan Shunpike [who is known to be innocent], for instance. ...You're making Stan a scapegoat, just like you want to make me a mascot. ...Either we've got Fudge, pretending everything's lovely while people get murdered right under his nose, or we've got you, 38 chucking the wrong people into jail and trying to pretend you've got [me] working for you!

Harry recognizes the error of trying to manipulate the opinions of others through pretense, whatever its form. Whether Fudge tries to convince people that there is no danger, or Scrimgeour tries to convince people that he's arresting dangerous criminals or working with a powerful ally, such pretense rests on the view that most important is what other people believe, not the facts.

A particularly wicked example of a power-seeking second-hander is Dolores Umbridge, who takes Fudge's policy of manipulating opinions to ghastly levels.

Fudge assigns Umbridge to Hogwarts to silence talk of Voldemort, monitor the other staff members, and prevent students from learning magic that they might use to undermine Fudge's power. She even physically abuses Harry for speaking up about Voldemort by forcing Harry to write lines with a magic pen that makes his hand bleed. Umbridge prevents her students from learning defensive magic because, as Sirius explains, Fudge fears that Dumbledore is "forming his own private army, with which he will be able to take on the Ministry of Magic." Eventually, Fudge grants Umbridge more power over the school by making her "High Inquisitor." As Umbridge grows more tyrannical at Hogwarts, Voldemort breaks his followers out of Azkaban and brings the prison's ghoulish guards—the dementors—under his control.

Umbridge is particularly nasty toward Harry as she attempts to shut him up. Umbridge first appears at Harry's hearing, where she challenges Dumbledore. Harry has been charged with using magic as a minor outside of school, which is forbidden. However, the reason that Harry used magic was to defend himself and Dudley Dursley from dementors. Dumbledore wonders why dementors, supposedly under Ministry control, attacked Harry. Umbridge mocks Dumbledore for this and encourages other members of the council to join her in making fun of Dumbledore. Thus, Umbridge helps Fudge in his efforts to discredit Dumbledore and Harry.

39 Harry later learns that Umbridge knew all along who ordered the dementors to attack: she did. Finally she admits that Fudge "never knew I ordered dementors after Potter last summer, but he was delighted to be given the chance to expel him, all the same." The fact that dementors enjoy destroying their victims caused Umbridge no hesitation.

In this case, Umbridge reveals her second-handedness in several ways. Even though she acted independently of Fudge's knowledge, such independence is superficial and based on her subservience to an authority. She accepts the authority of Fudge and the Ministry of Magic, and she therefore acts to suppress the facts about Voldemort; even though she does not tell Fudge about the dementors, she sends them based on Fudge's official line. She also uses violence (as well as deception and intimidation) against others in order to compel their actions—a theme to which we will return.

As Umbridge accepts the authority of the ministry, so she insists that her students accept what an authority tells them. When Hermione asks why they are not learning to use defensive spells, Umbridge responds with condescension: "Are you a Ministry-trained educational expert...? Wizards much older and cleverer than you have devised our new program of study." When Harry points out that the students need to learn defensive magic to protect themselves from Voldemort and his followers, Umbridge calls Harry a liar. Harry retorts, "I saw him, I fought him!" But Umbridge does not endorse a first-handed understanding of the facts based on one's own evaluation of the evidence. She again insists that students accept what an authority tells them: "The Ministry of Magic guarantees that you are not in danger from any Dark wizard."

The second-handed approach of uncritically accepting the pronouncements of an authority brings with it one main problem: an authority can be wrong, manipulative, or vicious. Umbridge is perfectly willing to accept and promote Fudge's baseless and paranoid assertion that Harry and Dumbledore are lying about Voldemort's return. Then, after the Ministry accepts the facts about Voldemort, Umbridge bows to the authority of the new regime as easily as she did to the old.

40 Finally, when the Ministry of Magic falls to Voldemort's forces and Voldemort installs his own puppet minister, Umbridge remains loyal to the Ministry's authority. When Harry and his friends break into the Ministry's headquarters, Harry sees Umbridge and her new office. The plaques on the door read, "Dolores Umbridge: Senior Undersecretary to the Minister; Head of the Muggle-Born Registration Commission." Just as the Nazis registered and persecuted Jews, so the Ministry of Magic under Voldemort registers and persecutes "Muggle-born" wizards (those born of non-magical parents).

Harry finds Umbridge interrogating wizards thought to be Muggle-born. Just as Umbridge falsely accused Harry of lying about Voldemort, based on the ministry's authority, so Umbridge falsely accuses Muggle-born wizards of stealing their wands, based on the same authority. Moreover, just as Umbridge subjected Harry to physical abuse and even the risk of death, so Umbridge subjects her new victims to torture, imprisonment, and threat of destruction.

Umbridge's behavior reveals the connection between a second-handed acceptance of an authority and the use of authority to punish. Harry and his allies seek to persuade peaceable people through reason. They resort to force only when attacked, in self-defense. When one relies on reason—logical evaluation of the evidence—one counts on others' first-handed ability to follow the reasoned arguments and independently check the evidence. But one who expects others to take the word of an authority, without independent verification, must instead rely on deception, intimidation, or, ultimately, brute force. It is no surprise, then, that Umbridge simultaneously accepts an authority over her, expects others to believe whatever the authority tells them, and exerts authority over others in the form of physical force.

Next we turn to the example of Voldemort, the ultimate manifestation of evil in the Harry Potter books. While his evil extends far beyond the vice of second-handedness, he is the extreme example of the power-seeking second-hander.

On the surface, Voldemort seems quite different from Umbridge. He accepts no authority over him but seeks to impose 41 himself as the authority. To his followers, "the Dark Lord's word is law."

Yet, like Umbridge, Voldemort uses force against others to get them to accept authority. Just after he regains power, he tries to put Harry under a controlling curse, which Harry resists. Voldemort says, "Harry, obedience is a virtue I need to teach you before you die. ...Perhaps another little dose of pain?"

Umbridge and Voldemort are similar in their efforts to subject others to authority. Are they fundamentally different in that Umbridge accepts an authority over her, while Voldemort believes himself to be the ultimate authority? No. Voldemort, like Umbridge, bases his life on the beliefs and views of other people. In seeking power over others, Voldemort makes others the focus of his life. In this sense, he is a second-hander through and through, just like Umbridge.

By showing Harry old memories from various sources, Dumbledore reveals Voldemort's past. When Dumbledore first meets Voldemort, who as a youth goes by his given name of Tom Riddle, the young wizard expresses his satisfaction at being above other people and able to control them: "I can make bad things happen to people who annoy me. I can make them hurt if I want to. ...I knew I was different. ...I knew I was special."

Dumbledore notes that, even prior to any formal instruction, Riddle "was already using magic against other people, to frighten, to punish, to control"; he had "obvious instincts for cruelty, secrecy, and domination." Riddle dislikes his first name because "Tom" is too common. Dumbledore explains, "There he showed his contempt for anything that tied him to other people, anything that made him ordinary. Even then, he wished to be different, separate, notorious. ...Tom Riddle was already highly self-sufficient, secretive, and, apparently, friendless." However, Riddle's "self-sufficiency" was not that of a first-hander, who reaches his own conclusions and achieves his own values. Instead, Riddle evaluated himself in comparison to others. He wanted to be different...from others. Separate from, but in control of, others. Notorious...in the eyes of others.

42 Dumbledore continues, "The young Tom Riddle liked to collect trophies. ...These were taken from victims of his bullying behavior, souvenirs, if you will, of particularly unpleasant bits of magic." Riddle stole objects from others in order to demonstrate (to himself) his superiority. Later, Riddle murders others to gain objects of importance from them. Dumbledore notes, "Voldemort had committed another murder...not for revenge, but for gain. He wanted...two fabulous trophies." One of those objects "had belonged to another of Hogwarts's founders." Voldemort likes to collect things, not by earning them but through force, and not because he enjoys their qualities directly but because they represent his superiority.

When Voldemort rises to power, he takes special delight in practicing the three Unforgivable Curses. Notably, each of these curses is about controlling others. The Imperius Curse enables one to control the movements and behavior of others. The Cruciatus Curse inflicts unbearable pain on the victim; prolonged exposure can result in insanity. And Avada Kedavra kills. These (and their counterparts in our world) are the ultimate weapons of the second-hander who seeks power.

When Voldemort overthrows the Ministry of Magic, he places within it a symbol of dominance—a statue showing "a witch and a wizard sitting on ornately carved thrones," structures composed of Muggles, "hundreds and hundreds of naked bodies, men, women, and children, all with rather stupid, ugly faces, twisted and pressed together to support the weight of the handsomely robed wizards."

Voldemort, however, does not merely wish to place wizards above Muggles; he wishes to place himself above all wizards. Voldemort sees Muggles as worthy of nothing but slavery to wizards, and he also condemns so-called Mudbloods and blood traitors. Though the statue represents wizards as superior to Muggles, even "pure blood" wizards are to be subjected to Voldemort's total authority.

Voldemort's entire motivation is to place himself in superiority over all others. His aspirations depend completely 43 on his position relative to other people. In attempting to place himself in power over everyone else, Voldemort makes his entire life utterly dependent on everyone else. This is the exact opposite of a first-handed approach, which centers on one's own judgment and values, relates to others through reason, and judges one's value independently. Voldemort is therefore an archetype of this particular sort of second-hander.

Another type of second-hander wishes to follow a power figure. Even though Umbridge accepts a higher authority, both she and Voldemort mainly want to exercise power over others. Some, though, are motivated mainly by a desire to prostrate themselves before power. This is true of some of Voldemort's followers. Even though they gleefully harm and control others, they do this primarily to impress Voldemort. A sort of mirror image of the second-hander who seeks power, then, is the second-hander who seeks to be dominated, a relative of seekers of social status.

Barty Crouch, Jr., the wayward son of the Ministry official discussed previously, and Bellatrix Lestrange offer two examples.

Crouch, in disguise, manages to deliver Harry to Voldemort. Harry escapes, but Crouch captures him again and intends to kill him. Crouch eagerly anticipates Voldemort's reaction: "Imagine how he will reward me...I will be honored beyond all other Death Eaters. I will be his dearest, his closest supporter...closer than a son."

Bellatrix becomes incensed when Harry dares to speak the name of Voldemort and suggest (correctly) that Voldemort's father was a Muggle. She too imagines that she "was and [is] the Dark Lord's most loyal servant." Only a short time later, however, when she fails to successfully complete one of Voldemort's commands, she begs, "Master...do not punish me." For Voldemort, punishment usually means the torturing curse. Bellatrix's relationship with Voldemort is one of masochism and delusion. Even after she provokes Voldemort's anger, she continues to claim, "He calls me his most loyal, his most faithful." That does not prevent Voldemort from nearly killing her in a rage. Later, Bellatrix believes that Voldemort has struck Harry dead: "'My Lord...my Lord...' She spoke as if to a lover."

44 Yet, as Dumbledore explains to Harry, "You will hear many of his Death Eaters claiming that they are in his confidence, that they alone are close to him, even understand him. They are deluded. Lord Voldemort has never had a friend." The only thing that Bellatrix truly loves is subservience to a powerful figure.

The First-Handers

We have seen several forms of second-handedness, from the drive for unearned social standing to the quest for power over others to the wish to be controlled. The common trait of all second-handedness is living one's life according to the opinions, expectations, or position of others.

Now we turn to the first-handed heroes of the books, those who think for themselves and choose their own values—including honest and mutually respectful relationships with others—based on what they independently understand to be moral and good for their lives. While all of the heroes act first-handedly (at least most of the time), three characters offer especially clear examples of first-handed living: Dobby, Hermione, and Harry.

Dobby pushes the boundaries of the magic that binds him to slavery, then he embraces his freedom. Contrast Dobby's independence with the servility of Winky. When Winky's master, Barty Crouch, Sr., catches her in a position that embarrasses him, he punishes Winky by freeing her. She cannot imagine living a life of freedom—making her own choices, free of the imposed will of others. "No, master!" she begs.